Are you thinking about Christmas already? Or perhaps putting off thinking about it? 😉

I have a new story for you, about one young woman’s run-up to Christmas. Remember the apprentice jeweller Jack Neave, angling for his first commission in ‘Luverly’? (Read it here if you missed that short story.)

Now I’ve written some follow-up fiction about his lovely customer – why did she want that necklace? Adelaide is young, inexperienced, newly married to the owner of an exclusive hotel, and there’s quite a lot at stake for her this season…

Speaking of exclusive, this story is only for subscribers. It’s my thank you, for your encouragement – reading and commenting on my stories this year 😀 (Keeping the story private is one reason why there’s no audio recording this month. The other reason is that my son has temporarily run off to Europe with my microphone.)

(If you’re not a subscriber and you want to read the whole short story, hit the button:)

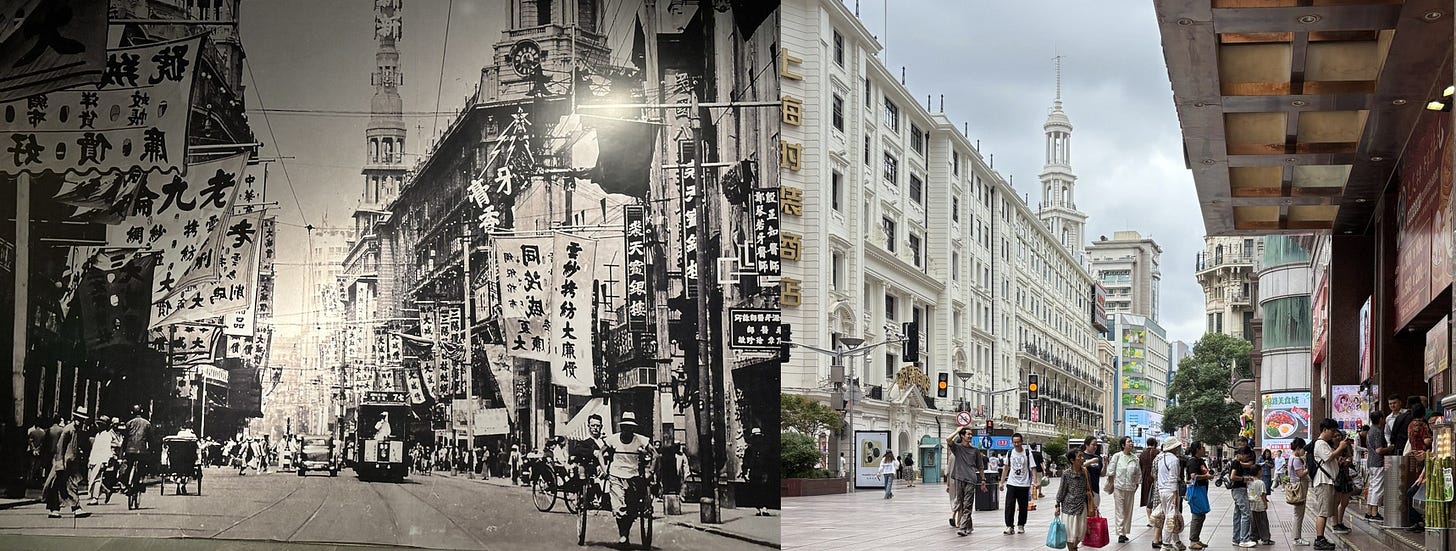

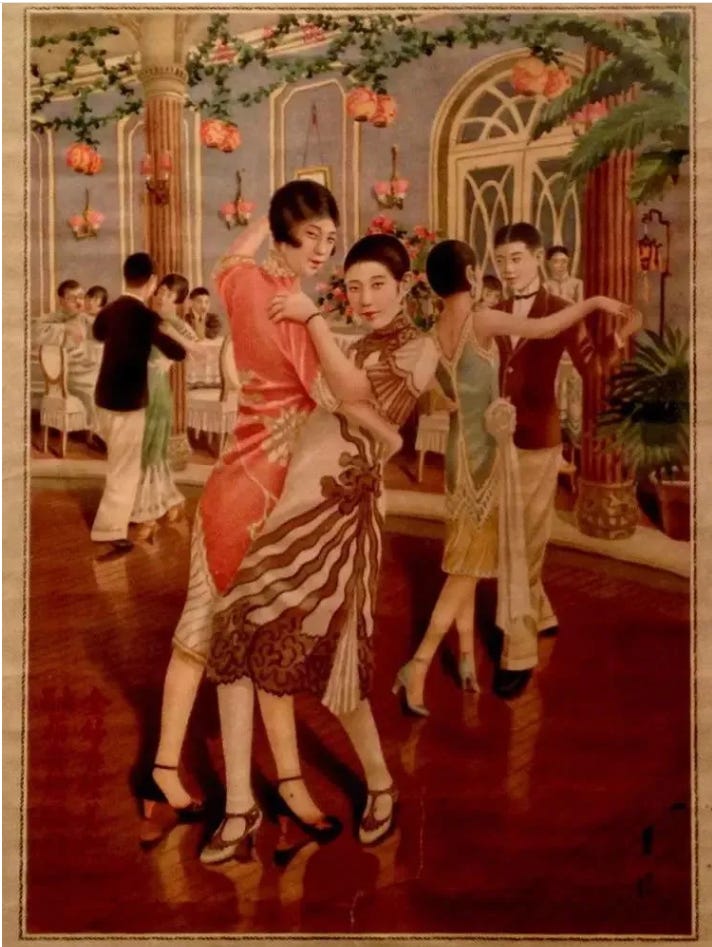

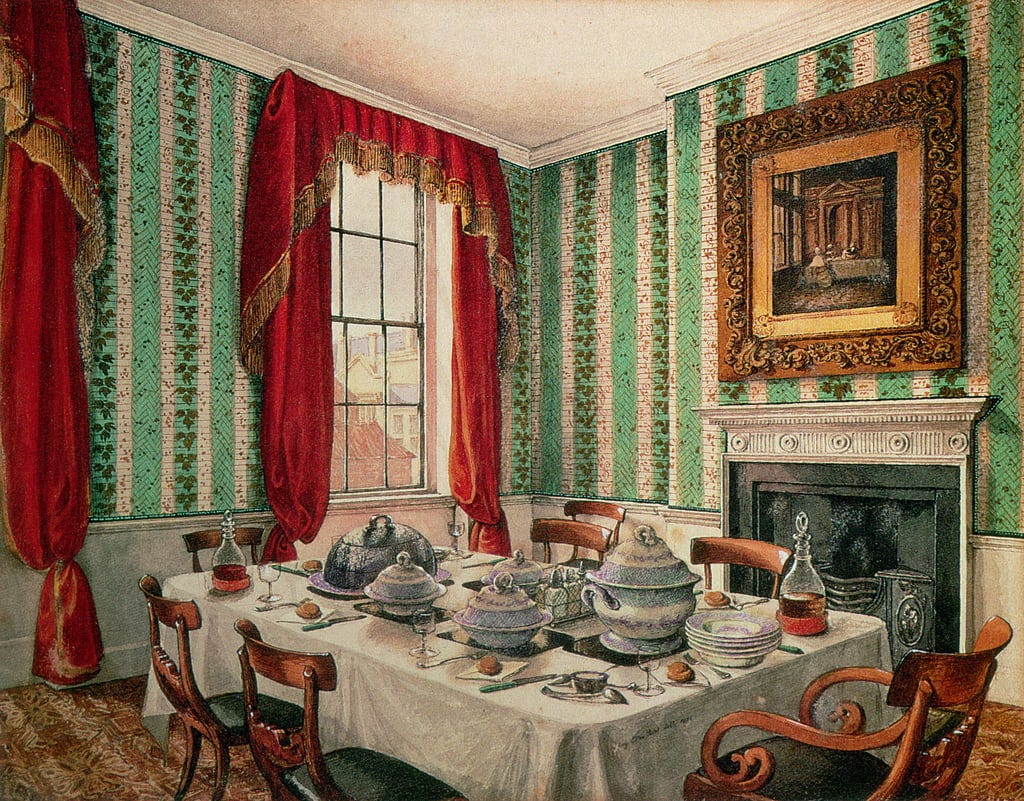

A Classy London Establishment

I based the hotel in this story on an actual London establishment – Brown’s Hotel, Mayfair. It’s not the biggest or most famous London hotel. But for the last two centuries, it has attracted some classy clientele. Queen Victoria was known to take tea there.

The hotel has also hosted many famous authors, including Mark Twain, Joseph Conrad, Rudyard Kipling, William Golding, Agatha Christie, A.A. Milne, and Stephen King.

Regrettably, both the hotel accommodation and the book on its history are out of my range – geographically and price-wise. So the characters in my story are entirely fictional.

If you’re not a subscriber, you’re welcome to sign up to read the rest of this story:

by Alison Lloyd

Mayfair, 1858

The jeweller called at the most inconvenient time. Adelaide Brown’s husband was closeted in the office with his accountant. The two men were nutting out their final numbers, prior to that night’s dinner for the financier. If the financier agreed, Brown’s Hotel would have the funds to maintain its quietly exclusive status.

Adelaide listened at the office door. The oak door emanated a solid and masculine silence, dense as the wood itself. The corridor was unheated. It had been a long time since her summer honeymoon; as the winter set in she was often shivery, almost ill. She felt the need for warmth, food and comfort.

Fred had asked her at breakfast what was the matter. Grateful for his care, she requested that he put another log on the fire. Instead of doing it himself, he’d rung for the butler. A tide of disappointment, murky as the Thames, welled up in Adelaide. Fred hadn’t bothered to exert himself for her.

She took a mouthful of tea to swallow her emotions, but it tasted wrong. The brew curdled her stomach.

Fred picked up a butter knife and slit open a note delivered that morning.

‘Aha!’

At first Adelaide thought the financier had granted the loan. Then they could go ahead and refurbish the old rooms, and extend the hotel to Albemarle Street. She wouldn’t need to worry about the dinner as much.

The dinner had been arranged after Adelaide suggested, weeks back, that she and Fredrick go to church, where the financier was a regular. Fred dismissed the idea initially.

‘I haven’t been in years. It’ll look like we’re chasing him.’

They were chasing him, Adelaide thought. But she saw a way round that.

‘I’m your new wife. He can put it down to my good influence.’

Fred took her fingers to his lips and kissed them. ‘I’m turning over a new leaf, eh?’

Then he turned her hand over and kissed the inside of her wrist, watching her. Desire gleamed in his eyes. He was so handsome when he paid her courtesies.

The church service was cold and uncomfortable. Listening to the Scripture reading, Adelaide made an unwelcome realisation. She tried to ignore it. As Fred introduced her to Mr Horace West, an imposing older gentleman with a Biblical beard, she tried to think only of Fred and the hotel. If she didn’t think about her apprehension, she hoped it would go away.

Adelaide invited the investor to dinner. Mr West was proving difficult to persuade but at least he agreed to the invitation. The details of the meal were in the hands of the butler and the hotel’s excellent French chef. Adelaide’s part, as she saw it, was to impress the financier. She didn’t want him to think her young and flighty and a risk to his investment.

However, the note that Fred read aloud over breakfast kippers turned out to be from the jeweller. He was coming that day with her new, finished necklace.

‘Perfect!’ She was excited, although she tried not to show it over-much. She wasn’t a child, distracted with bright baubles. Still, this was the first piece of jewellery made just for her. (Wedding ring aside. The plain gold band didn’t count.) And it had arrived just in time for the dinner, as she’d intended.

Fred’s eyes lifted from the note to rest on her. He smiled, tenderly and attentively. That smile had won her over during their courtship. His unflagging attention had made her say yes. Not his money, whatever her mother and her sisters said. Adelaide knew money alone wouldn’t make her happy. She’d relished her mother’s surprise. ‘Who knew our little Addy was destined for such things? And only sixteen.’ She looked at her daughter with wonder, as if she hadn’t fully seen her before, which in fact she hadn’t. Adelaide was actually seventeen.

Since moving into the hotel, she’d observed that Fred had the knack of giving undivided attention to anyone. Because of this, his staff liked working for him, and his guests felt at home. She told herself this was good; it boded well for the business. But she wasn’t convinced it boded well for her. She felt less special, as if she were another hotel guest.

Fred reached past the milk jug and touched her hand. He laced his fingers through hers, drawing her to himself. Her cold, anxious core softened a little.

‘I’m looking forward to this,’ he said. ‘Although no jewellery is as beautiful as you.’

She flushed. She hadn’t made a mistake marrying him after all.

She was looking forward to the necklace’s arrival too. She was hoping Fred would be pleasantly surprised at the quality she’d got, with his money, for just under two hundred pounds. She wanted to hear him praise her taste, the workmanship, the value of her choice.

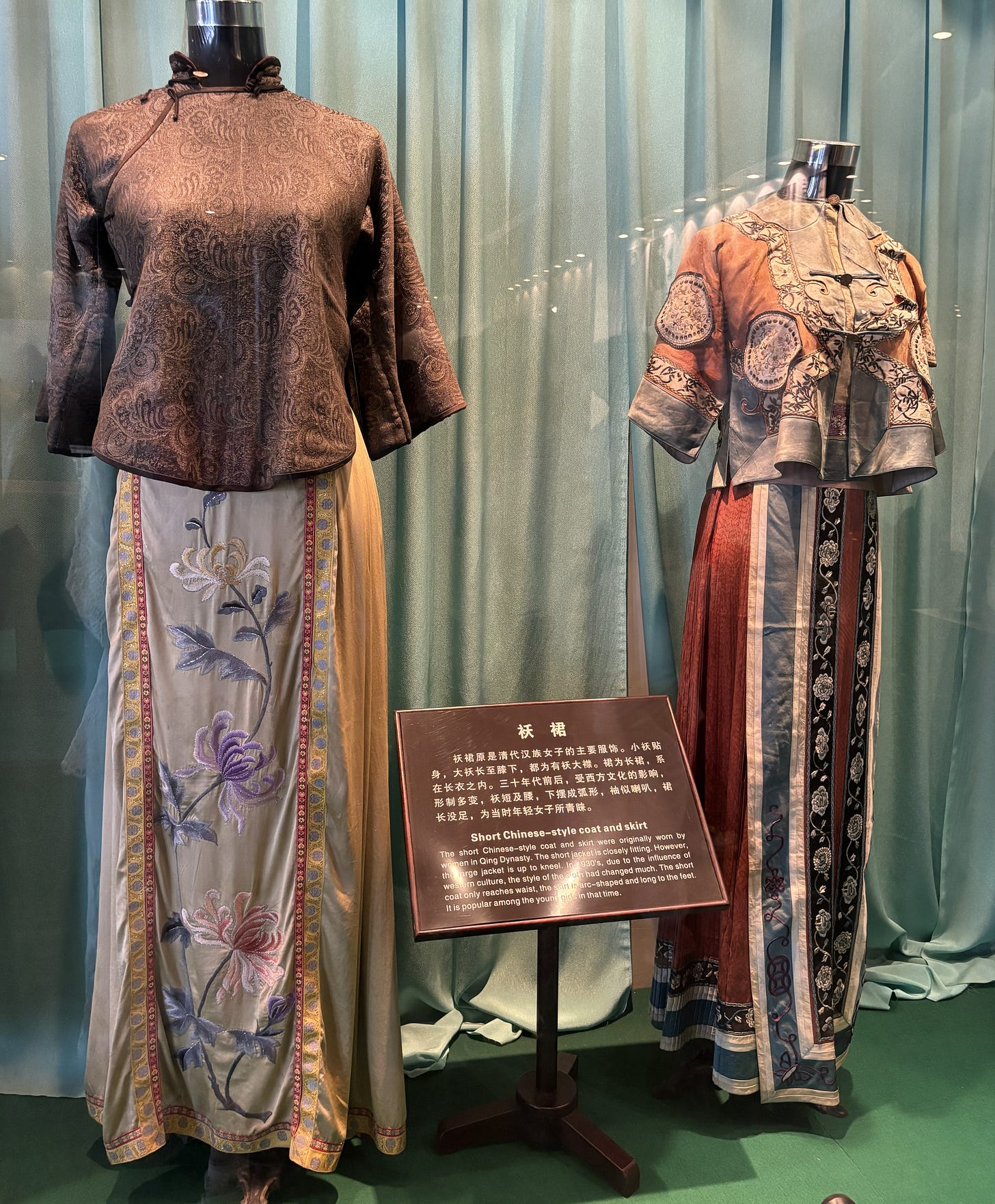

After breakfast, because the jeweller was coming, she changed into a low-cut dress, despite the cold. She touched her fingers to the smooth plane of her chest, below the hollow of her throat. She imagined him taking the necklace from the case and hanging it around her neck, laying the jewels along her breastbone, drinking in the sight of her. She imagined herself taking her his breath away.

***

But now Fred was too busy to receive the jeweller. From a window, Adelaide saw the apprentice and the master jeweller get out of a hackney, then she heard the reception clerk say that Mr Brown wasn’t to be disturbed, and he’d given orders for the parcel to be left at the desk.

She wanted to race through the hallway and call out ‘Wait! Wait!’ to the jewellers. That wouldn’t do. She had a couple of minutes grace anyway, since the concierge always entered deliveries in the register and wrote a receipt. She scurried down the corridor, to be confronted by the closed door of the office. She knocked uncertainly. There was no response.

The cold draught in the corridor wrapped itself around her bare neck and slithered treacherously inside her clothes. She felt sick. This was Fred’s first Christmas gift to her, and it didn’t matter to him as much as the business he was conducting. She didn’t matter to him as much as his business.

She had to show him.

She hurried to their private sitting room and tugged the bell pull.

The butler came, professionally polite, looking just past her, not a speck of dust or warmth on him.

‘Can you please inform the concierge,’ she said, ‘to send the jeweller here when he comes?’

‘Ma’am.’

Adelaide hoped it wasn’t too late. She hoped the butler would do as she asked.

He did. A few minutes later, the master jeweller came into the sitting room bearing a beribboned box on a velvet cushion, as if this was a coronation and Adelaide were the Queen. Behind him came the young apprentice – Neave, his name was. The youth went to close the door, only to find the butler had silently beaten him to it. The apprentice tugged his too-short jacket sleeves and licked his lips. He looked nervous. Adelaide was glad this call meant something to him. She wasn’t just another customer on the rounds, not to the young fellow anyway.

The jeweller made a fuss of getting the apprentice to move a side table into the window’s wintry light. He straightened the lace cloth and placed the necklace box on it.

‘Mr Brown won’t be joining us?’ he asked.

‘Regretfully, no. He has urgent business.’ She meant what she said about it being regretful. But she was also set on handling this herself.

The jeweller inclined his head to indicate he was sorry, then invited Adelaide to open the box.

Adelaide untied the ribbon and lifted the lid. Inside the box was a heart-shaped case of deep blue velvet.

‘How do I undo the catch?’ She looked up.

The apprentice was watching her eagerly, but said nothing, in deference to the master jeweller. The jeweller stepped forward – not in front of her, so she could still see the table – and flicked up a latch. He lifted the lid.

A wreath of gold leaves shone warm in the pale December day. Each leaf framed a purple amethyst – large enough to be costly, without overburdening the design. A festoon, the apprentice had called it.

‘Goodness,’ she said. ‘That’s very, very pretty.’

She looked at the apprentice. His eyes sparked with pleasure. And something more she thought – admiration. It wasn’t only the necklace that was pretty.

The jeweller bowed to acknowledge the compliment. ‘Would you like to try it on?’

‘Yes.’ She was decisive. Fred was not here, by his own choice.

The jeweller leaned in to lift the necklace out, but Adelaide stopped him.

‘Wait,’ she said, ‘let Mr Neave do it. He designed it, didn’t he?’

The apprentice’s head shot up, like it had when she first walked into his store. He grinned, then tugged his face straight in front of the boss.

‘Certainly.’ The master wasn’t best pleased, but too bad. The boy was pleased, and so was she.

Neave lifted the necklace from the box, and approached her slowly. Reverently, almost. His hands were shaking. She heard his short, restrained breaths – felt them on the skin of her neck as he leaned in to clip the ends of the necklace together.

Fred should be doing this, she thought. But he wasn’t. So she said nothing when the boy tweaked a leaf that wasn’t sitting straight and his hands brushed her breastbone. She let him look her over, and basked in his gaze.

***

She wore the necklace for dinner. If Fred noticed, he didn’t say anything. Nevertheless, as she took her seat beside the financier, she caught a glimpse of herself in the gold-framed mirror behind the dining table. Her grey silk dress glimmered gently, and the skin of her shoulders shone like the silk. The necklace caught the candlelight – its gold filigree was like fine lace. It looked like quality, she thought happily. And so did she. She felt the jewels, the not-insignificant weight of two hundred pounds, resting on her. They made her more substantial: Mrs Adelaide Brown, a person of note. She was no longer fourth in a frilly line-up of petticoats, a slip of a miss, whom everyone’s eyes skimmed over.

She knew she was young and inexperienced. She had no connections to help Fred, no name or title or money. But Fred had seen something in her that he liked, even if he sometimes forgot it. She was determined to remind him tonight. She’d begun to see how she could turn heads. She’d turned Fred’s, and she’d caught the attention of the jeweller’s boy. It was now up to her to sway the investor.

Through the turtle soup and sole with lobster sauce Mr West avoided talking to her. He and Fred and the lawyer talked about dogs, horses, and the Tories. West had one of those voices that was hearty and smooth as gravy, and he chuckled at Fred’s jokes. The perfect dinner guest. Yet Adelaide suspected he wasn’t fully onboard.

As dessert was served, when Fred was momentarily distracted by the butler, the financier turned to Adelaide.

‘Pardon me, Mrs Brown, I’ve been ignoring you.’

He asked how long she had been married. When she told him, he smiled a little sadly and told her she reminded him of his first wife.

Adelaide didn’t like to ask what happened to his first wife. She’d probably died in childbirth.

Mr West changed the subject. ‘Do you like living in a hotel?’

She didn’t say it was vastly better than the over-crowded bedlam of her family home. Or that she still felt like a guest.

‘Certainly,’ she said.

He indicated the exquisite pastries that graced the fine china in front of them. ‘Your husband serves a very fine repast.’

‘This is a very fine hotel,’ she said. ‘We want to make it finer.’

‘Quite.’ His voice was dry, acerbic.

She hadn’t quite engaged him. Yes, he was warm and courteous, as it was his business to be, but she didn’t know what he thought of her. She scooped a half-spoonful out of the pastry’s chestnut crème, but didn’t lift it to her mouth. Her stays were laced too tight. She felt queasy.

Mr West gestured with his spoon to the linen-clothed table, the heavy silverware, and Adelaide’s wavering reflection in the mirror. ‘I hope you’ll soon have a little family to adorn your home,’ he said.

Adelaide supposed he meant his words kindly. She wanted to run away, or retch. The Christmas reading in church had been about the Virgin Mary. The angel’s announcement that the young woman was ‘with child’ had tolled through Adelaide’s thoughts for weeks.

‘A child is not like a necklace,’ she said. ‘It’s not an adornment.’

Blessedly, Mr West was not offended. ‘I beg your pardon, Mrs Brown. You are right.’ He laughed, in a fond, reminiscent way. ‘They are a lot more inconvenient.’

She didn’t need him to tell her. Her mother had made it clear a long time ago. Adelaide had not been welcome, and she had no welcome to give this little thing in her, that already made her sick. This new leaf, unfurling within, could not be kept in a box like her necklace. She was afraid of it growing, bursting into the world and clamouring for her attention. She was afraid of its needs and expectations and hunger. She knew that hunger too well. She’d barely begun to fill it in herself, even when Fred lavished approval on her.

The financier was waiting for her to respond. She felt unmasked, exposed. She touched her necklace, to remind herself of where she was and to regather her composure.

‘I’m afraid so!’ she said. She meant to sound light and fond, like the financier’s tone. But something raw in her voice gave her away.

Horace West put down his spoon. ‘My dear,’ he said. His hand hovered over hers as if he would like to pat her. ‘I am not the angel Gabriel, to tell you not to fear.’ He smoothed his beard instead.

‘What I can say is this. I wasn’t inclined to give your husband the terms he requested. But for your sake – and…’ His eyes flickered briefly to her waistline. ‘Let’s call it a Christmas gift.’

West had spoken in a low voice. Adelaide looked across the large table to see if Fred had heard. Fred was watching, with a question on his face. She smiled at him, and nodded. His eyes widened with a look of wonder and reappraisal.

Adelaide thanked the financier. West brushed her thanks aside as if it were an extra serving of cream he didn’t need.

‘Every child is precious,’ he said. ‘Yet even our Lord wasn’t entirely welcome.’

Adelaide went completely still. Someone had at last seen right into her and spoken her thoughts. She was not alone, after all. She felt the leaf in her belly unfurl, and spiral, as if it had heard its name called. Adelaide’s fingers fluttered on her necklace. She touched the central pendant with her fingertip. A caress.

‘The most valuable gifts,’ Mr West said, ‘are often inconvenient.’

Hope you liked that. Another new story, with a whimsical twist, is coming next month! In the meanwhile, I’d love to hear what you think of this one. 1

Or you might like to tell me about your most significant Christmas?

Blessings and best wishes in this busy season.

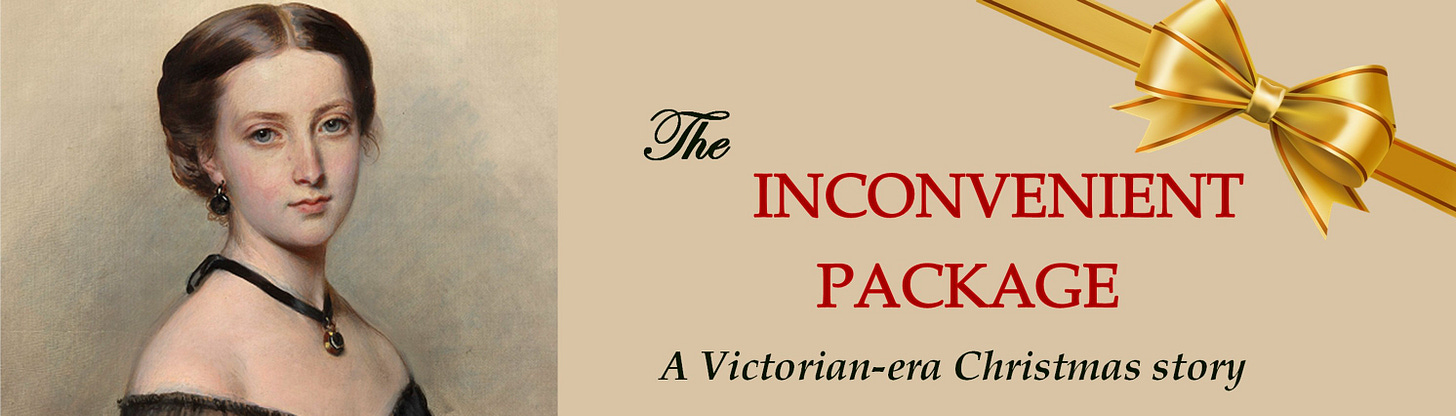

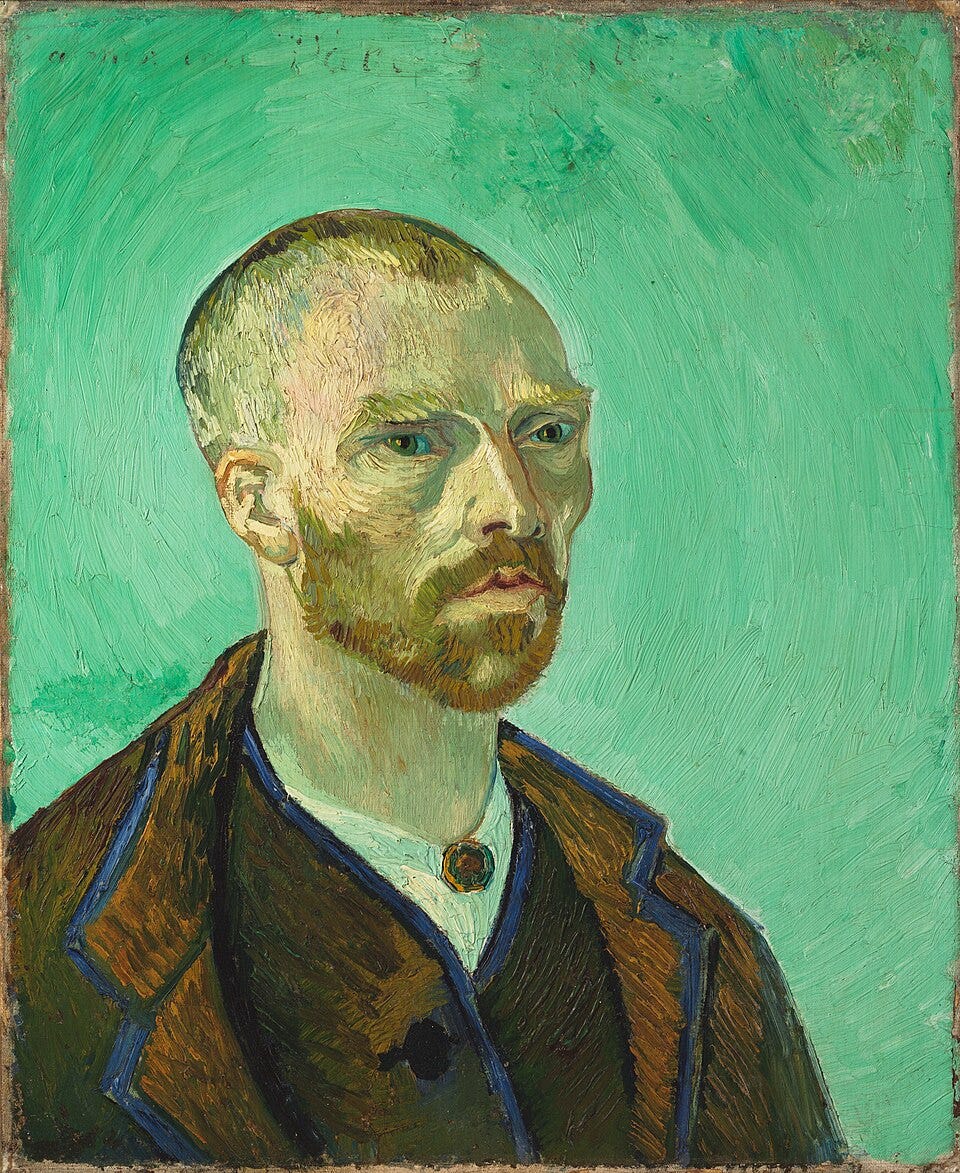

PS: Eagle-eyed readers may have noticed that for the story heading the necklace on the young woman isn’t quite right - it’s on a ribbon instead of being gold and amethyst. I went for the look of the character instead. If you’re into British history you may also have recognised Winterhalter’s 1861 portrait of Princess Helena, third daughter of Queen Victoria and Prince Albert.