The Twisty History of a Royal Art you probably Own

Author Alison Lloyd brings you history with heart - newsletter #51

Here’s a riddle, for women’s history month this March:

What art form was:

…banned, taxed and smuggled

…appears in paintings by Vermeer, Rembrandt and Van Dyck, but we don’t know the names of its creators

…relies for artistic effect on what’s not there, as much as what is

…was once a mark of wealth and royalty…

and is now in millions of homes, in an industrialised form?

(CLUE: try looking in your wardrobe.)

Want to know the answer?

It’s LACE.

Why would you want to read an email about lace? It’s beautiful, for one. And second, it was an art form created by women, appreciated by men.

History’s first lace appears on a portrait of a man.

This early lace was made by cutting pieces out of linen, as in the sampler below. It’s called reticella — not that you need to know, but the words rolls off your tongue so richly I wanted to share it!

Queen Elizabeth I incorporated the new product into Tudor grandeur. The Elizabethans used wire was used to hold out their lace ruffs and show off them off.

The circle of ruff extends from Elizabeth’s face like the Sun’s rays. She is shown as the centre and source of warmth, beauty, and goodness.

The Royal Museum, Greenwich

To which I would add — power, wealth, and control. That’s what this ornate geometric look suggests to me.

Before long, someone realised the cutwork technique was rather wasteful of linen, which was not a cheap product in itself. Craftswomen figured out how to make the patterns with no cloth, using just a needle and thread — punto in aria, ‘stitches in air’.

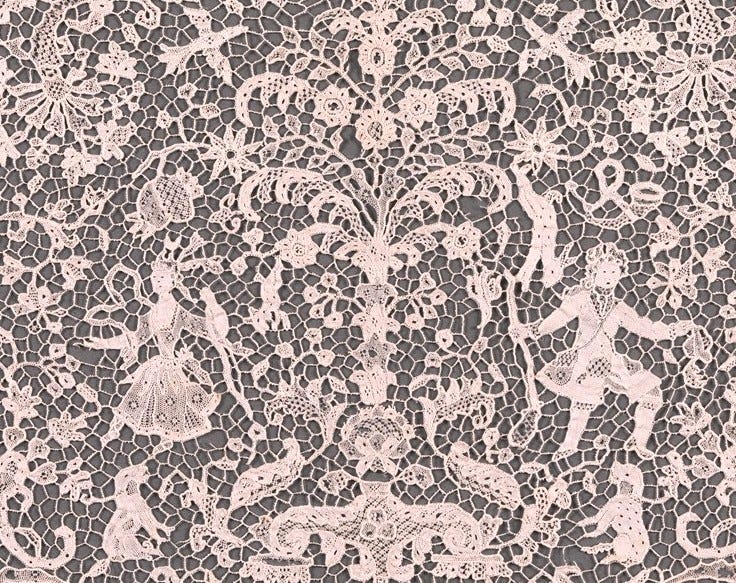

Needlepoint laces (like the delightful Met masterpiece above) can have as many as 6,000 stitches per square inch. Obviously, they took ages to make. Once again, unknown lacemakers innovated with a ‘faster’ technology. The new bobbin lace still took half an hour to make an inch.

By the time Vermeer painted his famous lacemaker, Flanders had become the epicentre of European lacemaking. The damp, cool climate helped prevent the gossamer linen threads from breaking, so Flemish thread was the finest in Europe.

Lace was not considered effeminate in its heyday. Men wore it as much as women. Why was that, when lace is such a delicate fabric? Most likely because it was also extremely expensive. Anyone who had fountains of lace frothing at their neck and wrists also had fountains of money. Lace was a luxury and a status symbol.

Apparently, lace goes well with armour:

Illicit Lace

Some governments objected to the expense of lace. In the mid seventeenth century, France banned foreign lace. In 1670 the government went so far as to ‘burn by the hangman a hundred thousand crowns worth of Point de Venise [Venetian lace], Flanders lace, and other foreign commodities that are forbid.’ Apocryphal stories have come down the centuries of lace smuggled under travellers clothes, and replacing returning corpses in coffins.

Colonial America wasn’t keen on lace either:

Taking into consideration the great, superfluous and unnecessary expenses occasioned by reason of some new and immodest fashions… [the Court] hath ordered that no person, either man or woman, shall hereafter make or buy any apparel, either woollen, silk, or linen, with any lace on it, sliver, gold, silk, or thread, under the penalty of forfeiture of such clothes.

The Records of the Colony of Massachusetts, 1634

Neither the Court nor the French prohibition had much effect. The French Revolution had a drastic effect, on lace as well as the necks that wore it. Lace finally dropped out of fashion — it was too decadent, and therefore dangerous.

But when Queen Victoria married in 1840, she chose a dress that became iconic. She wore white satin, rather than gold or silver, with deep ruffles of English bobbin lace around her neckline and skirt. Singlehandedly, the redoubtable queen restored the popularity of lace. Although only for women. And that’s still how it is now.

Who were the lacemakers?

I tried researching the people behind the art. Somebody with amazing skills must have developed these technical innovations and stunning designs. But Google gave me no names. So who made the lace?

Vermeer’s lacemaker may have been one of his daughters, art historians think. Lacemaking seems to have been decently profitable and highly thought of at the time:

Of many Arts, one surpasses all. For the maiden seated at her work flashes the smooth balls and thousand threads into the circle... and from this, her amusement, makes as much profit as a man earns by the sweat of his brow, and no maiden ever complains, at evening, of the length of the day. Jacob van Eyck, 1651

Two hundred years later, the lacemaker’s life had changed radically. Lacemaking was mechanised early in the industrial revolution, along with the rest of the textile industry. Industrial lacemaking was carried out by men on huge machines. Machine lace wasn’t initially as good as handmade, but it was cheaper, and it drove down the price of lace overall.

The maiden’s ‘amusement’ of bobbin lace turned into sweatshop drudgery. Little girls were shut up in ‘lace schools’, from 6am until late at night. ‘Five is too young,’ one lace mistress told a government enquiry. At six years old she could ‘beat it into them.’ A Victorian novelist described one lace school as

a den of thin, wizened, half-starved girls, cramped over their cushions.

Charlotte Yonge, The Clever Woman of the Family, 1865

The girls chanted folk songs to keep up the rhythm and speed of their work. Many of the rhymes are as macabre as the brothers Grimm:

‘Where’s the lady of this house?’ said Long Lankin.

‘She’s in her high chamber,’ said the false nurse to him.

‘Where’s the young heir of this house?’ said Long Lankin.

‘He’s asleep in his cradle,’ said the false nurse to him.

‘We’ll prick him, we’ll prick him all over with a pin,

And that will make your lady come down to him.’

They pricked him, they pricked him all over with a pin,

And the false nurse held a basin for the blood to drop in.

Long Lankin

You can imagine the little girls taking out their misery on their lace pillows, pricking it all over with their pins.

I did find the name of one British lacemaker, who won prizes for her naturalistic designs and exquisite craftsmanship. Emma Radford (1837-1901), ran a lace shop with her sisters in Sidmouth, in Devonshire. In 1878 she came second in a fan makers competition.

I tracked down the street where she lived and worked, but no further information about Emma Radford, or any other historical lacemaker.

Like the lace itself, the lacemakers’ stories are defined by absences. Their lives have disappeared into history, leaving only the intricate traces of their art.

My particular interest in this article was on the economical considerations of lace.

The banning of foreign imports of lace by Flanders in 1670 suggests to me that the government was concerned with maintaining social stability: cheap foreign imports might cause unemployment amongst local women producing lace in their homes, forcing them out into the fields or elsewhere to do dangerous and dirty work. Elderly women particularly might struggle in the fields and God knows what younger women might be tempted to do. All in all, it seems very nice of the Flanders' government to protect this cottage industry for the sake of women's dignity.

The attitude of the Colony of Massachusetts in 1634 seems quite different: Given that not just lace but other "immodest fashions" such as silver, gold, silk etc. were penalised, it seems more likely that their purpose was to stamp out frivolity, encouraging people to focus on what was wholesome. A modern equivalent, I suppose, would be the Australian luxury car tax which adds 33% to the price of a Porsche.