Welcome if you’re new (r old!) to this newsletter — I’m delighted you’re here. I’m author Alison Lloyd. In the Scroll you’ll find history for your heart — a thoughtful mix of fact and fiction.

Last month I got many positive comments on the new story about Jack, an apprentice jeweller in Victorian London. If you missed that short story (called ‘Luverly’), you can read it online here.

Good news — because of the readers who wanted more of him, I wrote another story. This one is about Jack’s mother, and her difficult choices in bringing up her son. If you like Dickensian settings, and/or character-driven historical fiction, I think you’ll like it.

Good news x2 — Jack Neave is a character in the new novel I’m working on, so there’s more to come. But it will be a while coming, I confess. I’m not a one-draft-and-done author. I like to get the words, the characters, and the story right.

So in the meanwhile, get to know Jack, a boy with promise, and attitude…

Hetty was hard put to feed her son. He was barely nine, but his limbs and his appetite were getting ahead of him. At tea he stowed the bread away like he was stuffing his trouser legs. When she watched him in the alley playing with the other urchins, fast as a pack of rats, she was afraid. That one day, he’d dart from her sight, and be lost to the hard, grey, streets.

But her Jack had another side to him. When he saw something he liked, he had the knack of being still for a long time. It was like he ate through his eyes, and filled himself on the shapes and colours. Look how he loved the pictures in that book of his father’s, how he drew them on his slate instead of his sums. He wrote the alphabet very pretty. In a few years she hoped his letters would get him a safe job, behind a desk.

Jack senior, the boy’s father, was like that too – his heart fell into his work. She used to think his spirit left his body and travelled through the patterns he made. Cor, he was a one for that. She loved it in him, and in his son.

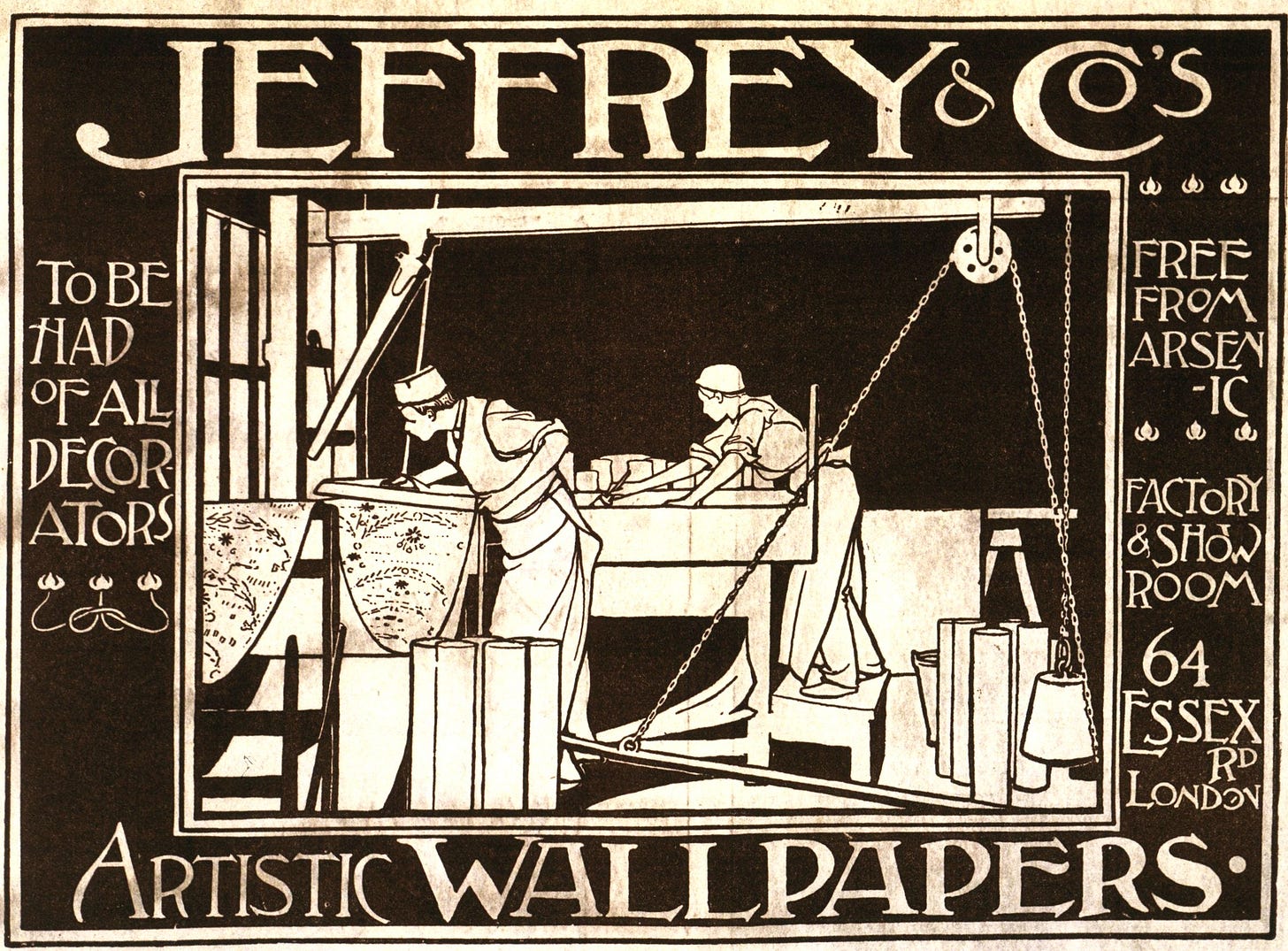

Jack senior done well, made a decent living as factory foreman. But in the end it cost him. His bones eaten, his life drained by the poisons at his work. That green wallpaper he was so proud of – it smelt like mouldy onion. Off. She was convinced it had got into him, although the factory said the sickness was none of their doing. When they lost him for good, she swore she’d never let the same happen to young Jack. She’d never let her son go to a factory.

Last week she’d seen a bit of paper up in the window of Dingley’s, the jeweller she passed by on her deliveries. ‘Wanted: an apprentice.’ The notice was written ever so nice, in fancy capitals with curls top and bottom. Hetty had stopped to look, just for the writing. She’d learnt to see through Jack’s eyes, while he was still alive, as if he’d lent her a pair of glass specs. So when something caught her fancy, when she was up the finer parts of town, sometimes she’d stop and look. She felt her husband was close, then. Standing at her shoulder on the pavement, nudging.

‘So ‘ow ‘bout it, Hetty?’

No.

Dingley’s wasn’t a factory. The jeweller had a workshop out the back of his store. But Hetty was no fool. Workshop, factory, they was sparrows and starlings – much the same thing. Just because the jewellery was so dainty, didn’t mean the work was easy.

Hetty could take in extra laundry, if Jack took on deliveries. He was tall enough to carry the baskets. Her hands wouldn’t thank her, but her son would stay in school.

‘Don’t stop and talk to nobody,’ she told Jack, loading him with the basket.

Inside, the hotel linens were snowy and folded, ticked off Hetty’s list. The cushion covers were tucked like a baby between sheets, so their fine brocade didn’t catch on the basket canes. A ragged cloth was tied over the top, so passers-by didn’t see what was inside. She warned Jack again about laundry thieves. She couldn’t afford to repay the hotel if she lost a piece.

Jack waved her away, itching to be gone.

‘Show me your hands.’

Jack flashed his palms at her.

She caught his hands and turned them over. The ‘u’ of his nails was free of grime. She felt a flush of pride at the care he’d taken to scrub up. His long fingers were just like his father’s. Clever hands.

Jack pulled away from her grasp.

‘They’re cleaner ‘n yours,’ he said. ‘Carter’s waiting.’

Hetty’s hands weren’t dirty. They were too clean – the skin was red and cracked from rubbing and soaking with the laundry. She let her son go.

All went well – the first trip, the second trip, the third trip. Jack was tired, but at the end of the week Hetty bought a small joint of pork with the extra cash.

‘Put some meat on your bones,’ she said.

He relished that. Her heart filled with grand satisfaction at the sight of him tucking in.

Jack spent the rest of the rainy Sunday doodling quietly on his slate. But he wiped the drawing off with his sleeve when Hetty came to look. That saddened her. His father had always shared. He brought designs and samples home from the factory just to show her when he was pleased with them. He used to look at Hetty herself like she was the loveliest piece in all London.

‘So ‘ow ‘bout it, Hetty?’ he’d say with a wink.

The next Monday, with the dirty linen, there was a note for Hetty, from the hotel housekeeper:

Dear Mrs Neave,

A bolster cover was missing from last week’s wash – green brocade with gold tassels. Could you please return it at your earliest convenience.

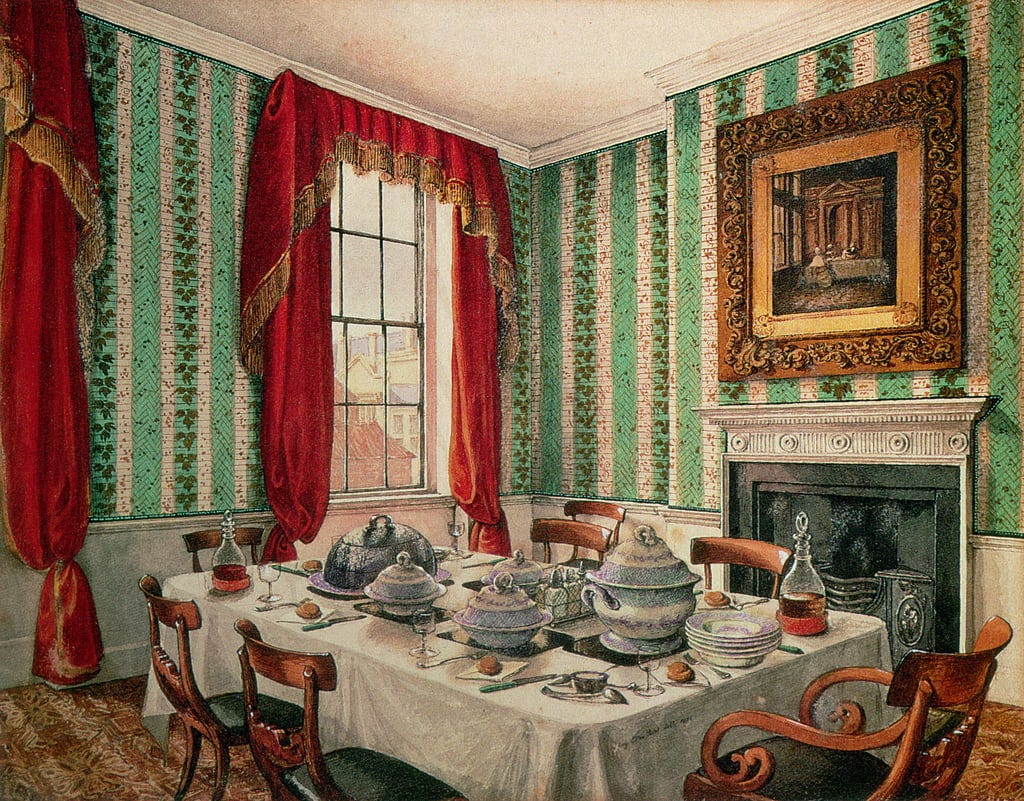

Hetty knew the one. A lovely pattern – a climbing vine over a gold trellis.

‘Look!’ Jack had said. ‘A beanstalk.’ When she read him that story he was such a little fellow, but he’d never forgot. The first time he was tall enough to see through a jeweller’s window, his eyes had lit like lamps. ‘Mam! Magic beans!’ He was very cut up that they couldn’t buy any.

Now Hetty was cut up. How could the bolster cover be missing? She’d got the wax off, then washed it separate because the dye ran. Once the wash was hung, she didn’t leave the yard. No thief got a chance to pilfer from her lines. She’d checked off her list as always, written in chalk on an old slate roof tile. Something must’ve happened during delivery.

She questioned Jack like he was up before a magistrate. Better her than someone else.

He swore he hadn’t talked to anyone, hadn’t dawdled anywhere. He said the hotel must’ve made a mistake.

Hetty hoped the manager found the piece soon. Otherwise she had a week before she’d have to sell something. The bed, maybe.

The manager did not find the missing cover. Neither did Hetty, although she looked everywhere at home – the tubs, the buckets, under the blanket, even down the back alley in case it had blown away. Not a single green thread.

But she did make a find in the back alley. The back fence was covered with chalk drawings. Her son Jack had turned the alleyway into a garden of art. A trellis, wound through with a climbing vine, blossomed with heavy heads of flowers. She was struck with the wonder of it, until she recognised the pattern.

Hetty dragged herself to the street, feeling like her boots were lined with lead.

‘Oy, Jack!’

He looked across from his game, his face pink and sweaty. His eyes slid back to the newspaper ball, ready to run.

Hetty went and nobbled him by the back of his jacket. ‘Inside,’ she ordered.

‘What are you? A copper?’ the boy muttered.

‘No, thank God,’ Hetty said. May it never come to that.

Inside, with the door latched, she put her hands on her hips. ‘Where is it?’

‘What?’

‘The green cover.’

Jack shrugged. His gaze skittered away from hers again.

‘Don’t you feed me any porky pies. I saw the back fence.’

Jack didn’t say anything. He scuffed his feet on the floor and wriggled, as if his clothes were itching him.

That’s where it is, Hetty thought suddenly.

‘Take off your jacket,’ she ordered.

Jack unbuttoned his jacket reluctantly, making a deal of every button.

‘And your shirt.’

He grabbed the fabric by the back of the neck and hauled it over his head. The bolster cushion slid out, and landed on the floorboards.

Hetty scooped it up. It was warm, and smelt of Jack. She checked it over – no damage she could see. She folded it, shakily, and held it to her chest, like she was trying to stop her heart falling out onto the boards with her son’s clothes.

‘Why did you do it Jack?’

‘I didn’t do nuffin’. Just looked.’

He stood in front of her, the thin bones of his shoulders jutting sharp and defiant.

‘You know it’s thieving.’

‘I seen how much that hotel got. There’s a room just for linen. With shelves –’ Jack stacked his hands, one over the other, above his head.

She knew it was true. She liked to see them herself, the neat, starched stacks, white as angel robes. Sometimes there were curtains down for turning and mending, in rich, heavy folds. Or bolster cushions as had been washed. Gentry could be careless with their food and drink.

‘It int yours.’

‘I hate our things.’ The anger was hot in his voice. ‘I hate how everythin’s dirty and old and brown.’

‘You mustn’t never nab anything Jack.’ She couldn’t stand it if he turned into a sneak. The other urchins on the street might be running pell-mell for a life of crime, but not hers. ‘Your father wouldn’t stand for it. You’re better ‘n that.’

She saw the boy was trembling on the edge of tears. She didn’t know whether he was sorry for being caught, or properly afraid for his soul.

‘Tonight you’ll go to bed with no supper,’ she told him. ‘Cos that’s what it’ll cost you to hop in a hackney now and get yourself to the hotel. With that cushion cover and your best apologies.’

She hoped this would hold everything together. That their life wouldn’t split like a worn sack and spill them onto the street. Maybe she should deliver the cushion cover herself. But she had a strong notion that Jack had took it, so he should return it. She hoped he’d do as she told him. He might keep it and lie to her. He might nab the bolster and sell it. Perhaps he’d believe the promises of some silver-tongued rogue for an easy life, and never come home.

Either way, she’d soon know. If he didn’t come home, he was lost to her.

Jack came back. He was tired and quiet, folded into himself. He looked thinner without the bolster cover wrapped around his chest. Flat and cold, as if the brocade had kept his heart and his hopes warm.

He handed over a note of thanks from the hotel housekeeper. Hetty hugged Jack in relief, but he was stiff as a poker to her touch. She released him. She couldn’t hold her son any longer.

The next day she scrubbed him up. ‘I want to show you something,’ she told him. ‘Then it’s your choice.’

She marched him down to Dingley’s. They stood on the pavement and looked in through the windows. Hetty pointed to the notice. ‘See that? They want a h’apprentice. If you show ‘em ‘ow you draw, I bet my boots they’ll have you.’

‘Really?’ Jack couldn’t drag his eyes away from the gleaming display in the shop window. Oh, she knew that look. His heart was in there already, tracing the shapes of the jewellery, falling into the deep pools of sapphire and the burning fires of ruby.

‘It’ll be hard work, Jack. Six days a week. You’ll only see me Sundays.’

She wondered if it would be too much. If he might rather stay with her. If she might be enough for him. She hoped.

He turned away from the window, but she could still see the glassy light in his eyes.

‘I can do it,’ he said, his shoulders set, his chin up. ‘And when I’ve learned ‘ow, I’m going to make one of them necklaces for you. Something properly beautiful.’

When she’d signed him away, she stood on the street and watched through the window. She could see his face, pale and glowing, in the shop interior. She could see him so clearly, now she’d let him go. But there was the glass between them, a separation.

She felt Jack’s father at her shoulder, watching their son. He was standing close enough to feel her pride and fear.

‘Ow ‘bout that, Hetty?’ he whispered in her thoughts.

How ‘bout that. She only hoped Jack found himself something properly beautiful.

Help yourself to more free fiction, as part of a promotion I joined. Click on the image above or here. Please note I did not select the books — there are a couple I find odd, as the books don’t seem to fit the historical theme. My pick would be the story about Susan B. Anthony.

I love hearing your thoughts and opinions. I know the comment button asks you to put your email in again when you aren’t a Substack user. If you don’t want to give it to them, email me back instead.

Leave a comment

Wishing you properly beautiful things until next month!

If you found this online or via a friend and you’d like a free monthly read, hit the button below.