Like a sprinkle of fairy dust on your day? Let me bring a bit of magic and whisk you away into the Victorian theatre scene.

Last month, I had a lot of fun writing new short stories. If you missed the two I posted, they’re here.

Now onto my latest research…

Before Disney there was…

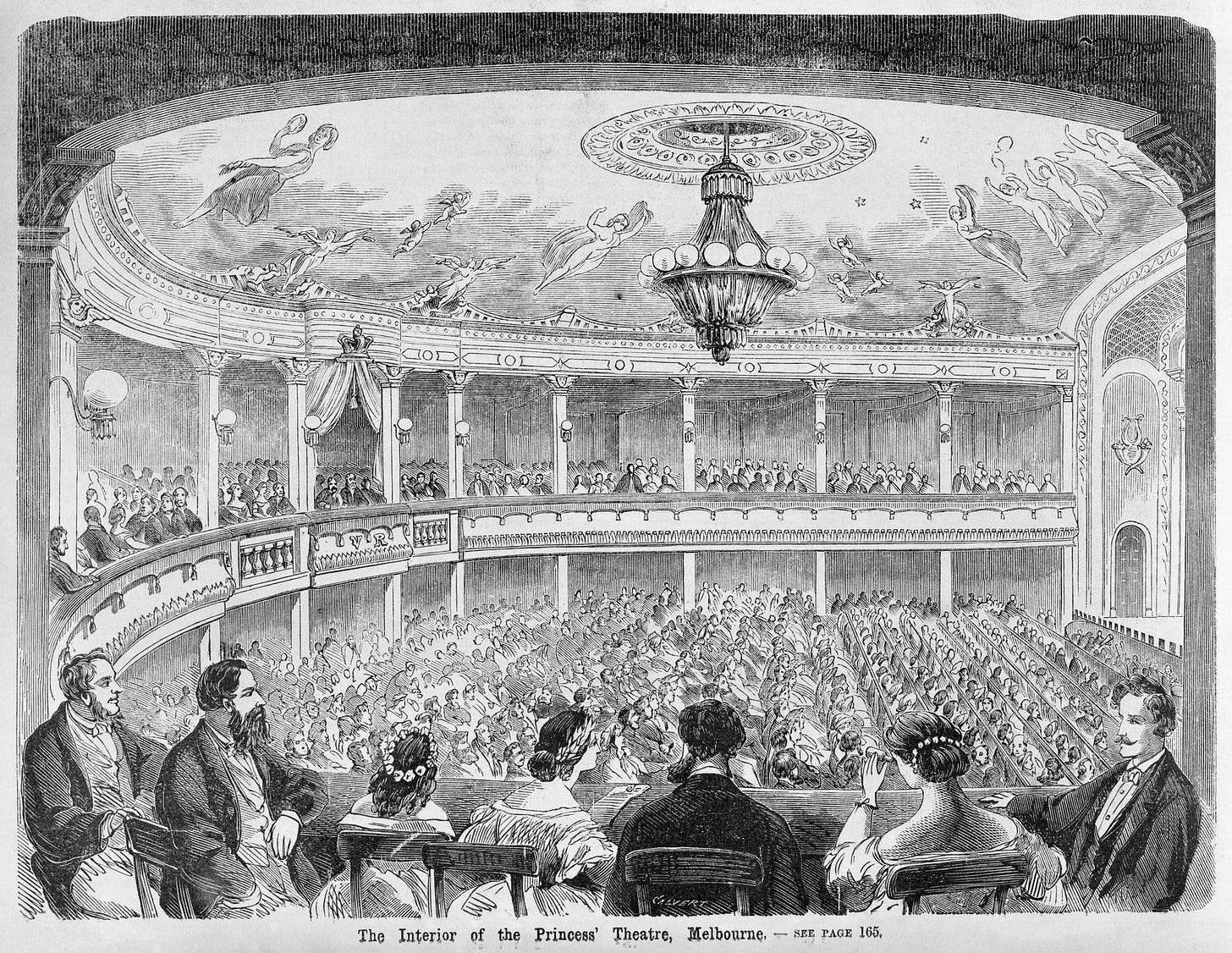

Before the movies, live theatre was the main form of popular entertainment. Local impresarios travelled to England to shop for big shows and big names, who performed in big, showy theatres, including in the Australian colonies.

Just like Disney, fairy tales were staple favourites - Aladdin, Babes in the Woods, Jack and the Beanstalk, Beauty and the Beast, and Cinderella. Late Victorian audiences loved fantasy. As one ballet fan wrote:

The mezzanine floor… underneath the theatre… is that mysterious region … the abyss to which the doomed palace sinks, and from which the fairy world arises.1

Women (and children) were cheaper to employ than men, so more of them appeared on stage. A 1900 season of Cinderella had 73 female performers, twice as many as the men and boys. Besides the lead roles, they included chorus ladies, ballet girls and children. Shakespeare’s boys-dressed-as-girls had disappeared. Victorian theatre liked it the other way around.

One of the most common supporting roles for women was the fairy, who guided the lead couple to happiness. She was often a trained ballerina – ballet was an essential part of every pantomime. Audiences knew that when the stage transformed into Aladdin’s palace, the ‘land of Fruits and Flowers’, or similar enchanted setting, the performance was about to break into song and dance.

Fairies popped up everywhere, including in an 1887 Robinson Crusoe production panned by the critics:

There is a principal fairy, embodied by Miss Julia Simmons with indifferent success, and there are a great many subordinate fairies, some of them with short feathery tails, at which the boys in the gallery laugh a good deal, and some with no tails at all, and with nothing else in the way of costume to speak of. 2

The Ballet Lady

…garbed in floating gauze to shapely knee

In graceful pirouettes of dazzling white

I cannot believe her human quite

O flitting fairy of another world

…wilt leave me now with brain so dazed and whirled

And angelwise soar off and disappear?

…I’ll see you after and we’ll have a beer.

The Bird o’ Freedom (Sydney newspaper) 7 March 1891

The Dark Arts

If you cynically suspect that these women were eye-candy for male audiences, you’d be right. Ballet girls and fairies were scandalously clad, by Victorian standards. An 1874 newspaper considered ‘modern ballet’ to be ‘degraded’.

Behind the bright lights was a shadowy backstage world. French writer Theophile Gautier, who wrote the storyline of the ballet Giselle, also wrote pityingly of the Parisian corps de ballet.

The world doesn't exist for them.. they know only the theatre and the dance class. They spend their mornings doing exercises in a gloomy darkness, lit with a red glow from smokey lamplights… They are surrounded by an artificial nature: oil-fired sun, gas-powered stars, Prussian blue skies, forests made of cut-out cardboard, palaces made of fabric.

Wages were low and schedules exhausting. Worse still, Gautier wrote, ‘not all slave markets are in Turkey. Here in Paris, in the middle of the 19th century, they sell more women than in Constantinople.’3 He said the brokers were often the girls’ mothers, seeking economic security for both their daughters and themselves.

Pets of the Public

I haven’t turned up any evidence suggesting the sale of sexual favours was as commonplace in Australian theatre. Although an 1882 NSW Royal Commission does mention crowds of admirers and hangers-on around stage exits – as a fire hazard!

Female performers were widely admired and celebrated, in books, postcards and the press. An 1888 publication featured 25 favourite actresses. Pets of the Public – a Book of Beauty, is a rather patronising and pukey title to our ears. And the text is pretty florid. But the author clearly admires these women for more than their figures and faces. Audiences were moved and enchanted by their performances.

Miss Nellie Farren is truly a pet of the public - an airy, tricksy, dainty sprite who charms without apparent effort and delights everybody in her audience… The Melbourne people were so smitten with her performance of Edmond Dantes in Monte Cristo, that they would not let the piece be removed.

By sheer hard work, indomitable courage, and unremitting industry, Miss Nellie Stewart has conquered the leading position in the world of comic opera… Her creations have satisfied even those querulous tourists [in] whose cockneyfied belief no good thing can originate out of London.

Pets of the Public, 1888, pp 23, 29.

What they have to do with us

Why is this history worth revisiting, other than as an entertaining diversion? A standard answer these days is to decry patriarchy and colonialism. Colonial society is rightly criticised for its prejudices. The sexism and racism in surviving theatre scripts are eye-watering. But I think it’s too easy and simplistic to view nineteenth century white men as villains in a melodrama of social progress. It misses something worthwhile, a valuable insight into ourselves.

We still have things in common with those days. Film has largely overtaken live theatre in popularity, but celebrity and fairy tales still have a shine for us. While the costumes and the lingo have changed, human nature hasn’t. We want to be enchanted, transported, and we love the people that do it for us. I think it’s spiritual. We may not believe in magic but we long for other-worldly wonder, and we love a touch of fairy dust.

Wishing you joy and transformation 😊 Until next month, I shall away!

Behind the Scenes: being glimpses of the public and private life of the ballet girl, 1900. p18.

Argus, 1 January 1888? Cited J.V. Fantasia ‘Entrepreneurs, Empires and Pantomime’, PhD Uni of Sydney, p82.

Thank you to https://gl-tch.org/giselle/cards/the-corps-de-ballet for this translation.

Such interesting information, thank you Alison.

And yes, we still need to be entertained and transported to a world of imagination, while treating all performers with dignity and respect