This email has some new, creative pieces! As a change from the hearty diet of history I’ve dished up in the last few newsletters.

For Oz and US readers, it’s Mother’s Day this Sunday. Scroll below for

a 000-sized meditation on becoming a mother. Only 87 words! So even the busiest parent can fit it in

a new short story about families and Mother’s Day

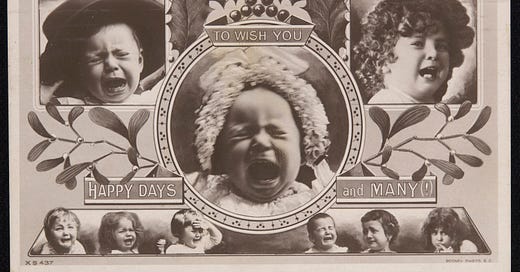

but first a bit of historical fun:

I’m in the middle of an online challenge, for a bit of creative pep — write a story a day in May. (Here’s the link to the prompts, if you want to join in). I’ve done six so far :) and I’m keen to share a couple here.

You might not think of yourself as a writer, or a mother, but there’s every chance you belong to a family. So I hope these stories warm your day.

This was written under a 100 word limit:

Newborn

You are a small, scrunched knot, unbunching, kicking into the light and new life. You jerk, stab a foot upwards — you haven’t quite got the knack of it. I haven’t quite got the knack either. I'm coming to terms with you. You’re coming to terms with me, and all there is around us.

You fling a punch – your fist startles open, hailing the world, and then you scrape the air with minute fingernails.

Hail, my own child. Already, you're remaking everything. You've remade me.

The next piece is fiction — I don’t have daughters. Although the necklace that got me writing really exists.

Mother’s Day

Mother’s Day is meant to be celebrated. Before the drive to Mum’s, I’m taking a minute, while the kids dither. I’m looking for the necklace I want to wear. It’s a string of seed pearls – a gentle, unassuming loop of imperfections. The necklace is long enough to fall between my cleavage and make an occasion of my clothes, without overdoing it. Gently luminous, the seed pearls say, ‘I’m here’, without the expensive, flashy aggrandisement of gold. If they were here, that is. Which they’re not.

The pearls are from Auntie, who wasn’t technically my aunt. There were several strings, a set, redolent with her French perfume. I remember how luxurious and generous the scent was, dignified and queenly. So are pearls. So too was Auntie, in her way. She wasn’t pompous, but she was tall, a red-head, and generous. She gave me the pearls well before she died, when she could have kept wearing them. I wasn’t her niece, not even her god-child, just the angsty eldest of her friend. Auntie wore the full set together, whereas I only ever wear one or two at max. One has broken. The other two, at the moment, have disappeared.

My jewellery is in a jumble. I keep it in a box given to me by my grandmother, who hand-painted the plywood with uneven daisies, and so I treasure it. A treasure box. I swirl a finger through the chains and brooches. You wouldn’t think in this day and age women under 70 wear brooches. I do, since they’ve been given to me – I find them handy for holding a top together, or a scarf in place. But they’re a prickly lot. The silver pins scratch and rattle. They peck at my finger, defending their patch. The costume jewels are glassy to the touch, reflecting the window light. The box smells of stirred dust, from the velvet lining.

Through the windowpane I hear a skitter of footsteps, like a handful of tossed pebbles. Whose footsteps are they? When I crane my neck, my line of sight gives me a glimpse of my eldest. She should be getting ready too. Or we’ll be late, and that’s awkward, because one of my siblings will get tense about feeding their children, who are young and can’t wait, and so their needs must come first. Families.

What’s my daughter doing in the garden? I’ve already got my matching shoes on – they’re pale suede, and the grass will be dewy. I leave the jewellery box spilling its treasure over the side, like a pirate chest. I go out and cross the grass, in wan sunlight, to the bench in the corner. My thirteen-year-old is hunched, arms around knees, head tucked, holding some hurt tightly together. Her elbows bristle at awkward angles like a badly folded cardboard box. Her sister calls her Flat Stanley. It’s mean, but I can see where she gets it from.

The paint on the garden seat is peeling and the patches of bare wood have a greenish tinge. I sweep my skirt up and squat by the seat instead. My knees click. My daughter shudders in revulsion.

‘Beautiful –’ I begin. I smooth her back and she shrugs my hand away. ‘What’s the problem?’

‘I hate her. I wish I was an only child. I wish I didn’t have a family.’

I feel a prickliness in me. Look, I want to say. You don’t make it easy either. Don’t spoil everyone’s day. Don’t spoil mine, for goodness sake.

‘Did you lock her out of the bathroom?’ I ask.

She glares at me with red-eyed hurt. ‘She said I was ugly. She never shuts up.’

My guess about the bathroom was right then. Tit for tat. ‘She didn’t mean it. She doesn’t like being locked out.’

‘She did mean it.’ My daughter buries her head and clenches her arms over her ears.

‘I’ll speak to her, but she has to get ready. So do you. We’re going in five minutes.’

I say it even though I know it will take longer for my daughter to untangle. Five minutes is wishful thinking.

‘I’ll speak to her later,’ I say, placating. ‘You don’t have to take it to heart. You’re not ugly. You’re beautiful.’

She is. She has her moments, when life flows through her, and she seems to refract and intensify every colour in the prism. Even if now isn’t one of those moments.

I lift her curls off her neck. ‘Your hair is so shiny,’ I tell her, ‘it’s like gold.’ I’m trying to soothe her. Her hair is more like copper, really – tawny, reddish.

She sniffs. I fish in my pocket and hand her a tissue.

I wouldn’t have chosen the top she has on. Not warm enough, for one thing, and the cropped look accentuates her skinniness. But it’s a sweet blush colour that suits her. Of course she’s ready, other than the tear-stains. Underneath them, she wants to go. She wants to be hugged and complimented by her Nanna, and to play with her cousins. She wants to belong. To be loved. That’s the pain she is guarding so fiercely.

It's my job to coax it out of hiding and kiss it better. I sigh to myself. Ten impossible things before breakfast. Before Mother’s Day lunch.

‘I know you’re upset,’ I say. ‘But I’d appreciate your help. I’ve mislaid a necklace.’

She tosses her head and turns her face away, resting it on her knee.

‘Not that thing Dad gave you.’ At least she is talking to me, even if not facing me. ‘It looks like a squashed insect.’

Thanks, kiddo. I know the one you mean. But there’s no need to turn the insults back on me.

Perhaps its envy. She and her sister have always lusted after my jewellery. At least they did when they were little, until they broke one of Auntie’s strings of pearls. I hid the jewellery box for a few years after that. Then pre-teen cool debunked my status in my daughters’ eyes, and I was replaced with the professional glamour of screen stars and influencers.

‘Not the one from Dad,’ I confirm.

‘How can you lose jewellery?’ Her accusation is addressed to the back fence, but the back fence redirects it to me.

‘I’m not sure.’ It is frighteningly easy to lose things, even things you love. They go astray somehow, in the jumble and prickle of life.

I don’t say this. I sit on the bench beside her, never mind the slime, and wrap my arms around her arms and breathe into her hair. ‘I love you, beautiful. Come inside. Give your mother a hand.’

I feel her angles soften, just a degree or two. I tuck her hair behind her ear, and kiss the young skin of her cheek.

She heaves a put-upon sigh. Then she springs open, like a clasp, and jumps up. ‘All right.’ She flings the words over her shoulder and runs back to the house, leaping wet patches of lush grass.

I’ve remembered where the pearls are – at the back of the sock drawer, where I put them out of my daughters’ sight. It must be that long since I’ve worn them. I get my daughter to look for them, while I change my skirt, because it’s stained, as I suspected.

My daughter finds the necklace. She twines the pearls around her fingers, touches them to her face and takes a deep breath of them.

‘They smell like Nanna.’

Like Auntie, actually, who gave Nanna duty-free bottles of scent. They are real pearls, organic, and that’s why her perfume has seeped into them. The lingering scent of the dead.

My daughter holds them out to me, arm’s length. She ferrets in the back of the sock drawer again, for the other string and slings it to me on one finger, as if she’s avoiding the contagion of oldness. ‘Only two?’ She frowns.

I suddenly think it’s not the age or style of the jewellery that’s bothering her. It’s guilt, and grief – the memory of the broken strand.

‘Mm. Yes.’ I take the pearls from her, holding the string between my two hands like a wreath. ‘Here, stand still.’

I lift the necklace over her head, and place it over her shoulders, like an honour bequeathed.

She looks down at the seed pearls, resting on the pale pink T-shirt, and runs a finger along the gleam of them. I kiss the top of her head.

‘Ready for Nanna’s?’

She nods.

I think: yes, we’re ready. Here we are, this string of pearls, one generation of women after another, none of us a perfect sphere. We are half-formed, opalescent, lovely, and connected by a thread.

Over to you

If these stories touched you, you could write your own little piece, for your kids, or your mum, or your spouse. You can say a lot in 100 words. Maybe write about when you first saw your child, or your first memory of your parent. Worth a try?

Also, if you enjoyed any of this, give it a like (at top), or write a comment. It helps other people find the Scroll and enjoy it too. And it inspires me!

Happy Mother’s Day to you all, mothers, daughters and sons. I leave you with a bunch of autumn flowers from my garden. Until next month.

If you’d like to receive more fresh fiction from me, and you’re not already subscribed, do it here:

I enjoyed your story about the necklace Alison. It was a great example of diplomacy, tact, and mediation in absentia, whilst still getting the desired outcome. It was touching too of course.