This is the Scroll, newsletter of author Alison Lloyd. If this is your first time reading, I’m glad you found me. You’re in for a brief burst of history with heart — fun, fiction, and inspiration. Feel free to write back — I love hearing from people!

I also love a stylish hat on a man. It’s dashing and debonair. Last week in my city we had the Spring racing carnival, and handsome hats abounded. Scroll down for more hattitude, from the top hat era:

a hat that helped make Australia

dangerous and wayward hats

and a hatless but stylish video on ‘The Beauty (and Brutality) of Leonard Bernstein’

Hats had their heyday in the nineteenth century, when no self-respecting man, woman or child was seen outdoors without one.

There were hats for all occasions:

Why special caps for smoking, you might wonder? The answer: so men’s hair didn’t smell of tobacco. If you think these caps look kind of Oriental, you’re right. Smoking was an exotic, private luxury for the Victorians — a chance for a man to lounge around on his ottoman and imagine himself a potentate.

Top Brass

At the other end of the occasion scale, was ultra-formal wear like this bicorne:

This hat was part of a suit worn in Queen Victoria’s court by the Australian politician William Wentworth, about 1854. (Ironically, Wentworth was the son of a convict woman, sent to Australia for stealing ‘wearing apparel’.) On his 1855 trip back to Europe, Wentworth persuaded the British government to pass a constitution for New South Wales, allowing the colony its own parliament. So this hat helped make the future of Australia. Incidentally, the bicorne demonstrates where the expression ‘top brass’ probably came from. The higher your rank, the more shiny metal on your hat.

The Topper

Court dress aside, the top hat was boss. Did you know they weren’t always black?

Top hats weren’t the most convenient headgear. They had a habit of blowing off. They were valuable, and several deaths occurred when owners chased their hats onto railway tracks or into water. Top hats were sassy and arrogant items that seemed to have a mind of their own:

Having made a rush of a hundred yards or so in a straight line… it suddenly bolts up against a wall and there reposes… Sometimes it squats right in the mud, over which it has been a moment before rolling with mischievous delight…for the express purpose…of deceiving its pursuers [that it is] willing to submit to capture.

Preston Chronicle, 18431

Top hats also required frequent brushing and they were awkward to store. Really, they were somewhat dysfunctional. But that was the point! A man who could afford a sleek, gleaming, well-groomed top hat was a man with money, and servants, at his disposal. Top hats were a mark of wealth. And power.

The British House of Commons had written rules about the wearing of top hats. Unlike in private homes, hats were to be worn when seated. They were taken off while entering and leaving the chamber. The hats, and the rules, were a way of enforcing ruling class dominance.

In an assemblage such as the House of Commons…the barriers of ceremony cannot be guarded too carefully. For once they are swept away, the rules of good breeding will act as feeble restraint on those whose rough manners are even now becoming rather embarrassing.

’The Great Hat Question’, The Standard, 23 March 1882

To Cap it Off

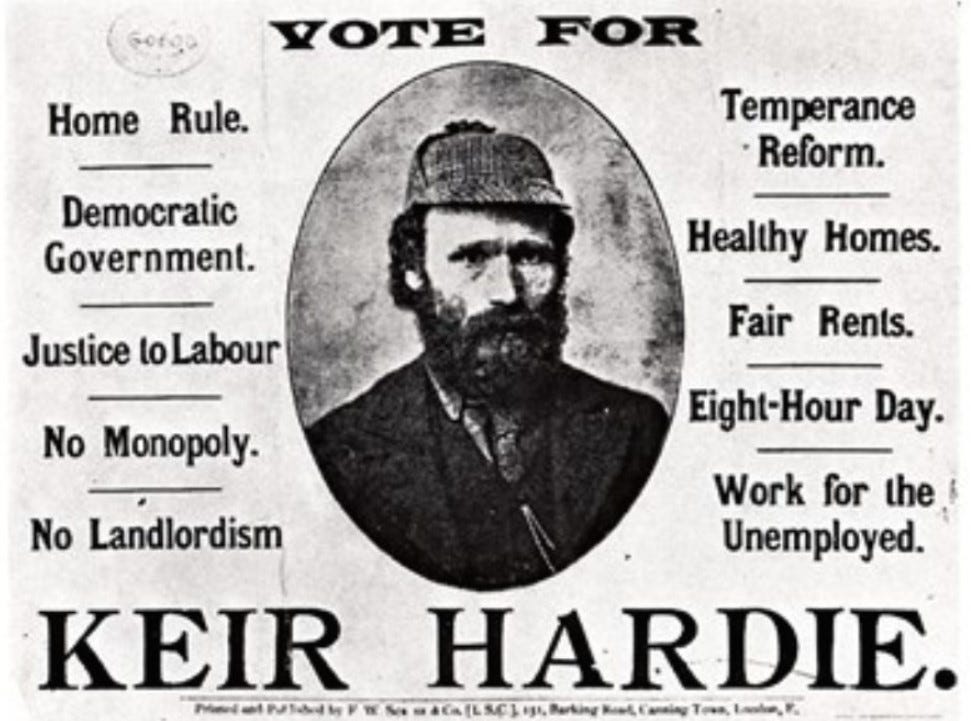

Lesser hats were not so upper crust. Caps were alarmingly revolutionary, a reminder of the French revolution and those rolling aristocratic heads. In 1892, British Labour MP Keir Hardie caused an uproar by wearing a cloth cap into Parliament.

‘The House is neither a coal store, a smithy, nor a carpenter’s shop,’ the Daily Telegraph blustered.

But some folk liked it.

Working men candidates do not want to pose as country squires, and miners from the pit’s mouth do not want to undertake the role of men of fashion. Their mission should be made of sterner stuff. I, therefore, hail with unfeigned pleasure the advent of the cloth cap.

Letter to the editor, Reynold’s Newspaper, 28 August 1892

How the style pendulum has swung. Now even conservative leaders don the headgear of ‘miners’ and ‘working men’.

I guess they want us to think they’re made of ‘sterner stuff’.

Hats matter! They signal the wearer’s desired identity. They give a talking head the authority to speak for others. Hats still rule.

The Beauty (and Brutality) of Leonard Bernstein

Speaking of style…A new film on Leonard Bernstein is coming out in a couple of weeks. A person near and dear to me recently posted this entertaining and well-crafted look at Bernstein’s creative life. If you like the video, there are more coming on other cultural icons.

New fiction from me next month! Until then, hats off to you, dear readers, for your appreciation of history and good stories — heady stuff.

This quote and the information about the parliamentary politics of top hats comes from ‘If you want to get ahead, get a hat’ in the Journal of the Canadian Historical Society, 2/2014.

Hi Alison. Learnt and loved this edition- the story of Hats- mostly men's and Bernstein's talents

Thank you Geraldine