Here’s an intriguing story about the pointy end of art and politics. (And hats.) Scroll down to meet a sixteenth century French refugee…

her beautiful books and the deadly serious stakes she worked for

plus related reading you might enjoy

and a completely unrelated story/poem from me

Stitches in Time

I came across this striking woman recently:

She’s quite stylish and Elizabethan isn’t she? She is Esther Inglis, calligrapher, embroiderer and bookbinder (c1570-1624).

When I saw her I thought — great, a talented historical woman who loved books; I’ll share this in the Scroll. Turns out, hers is not just a nice story. She was more than a woman making lovely art as self-expression. Esther Inglis wielded pen and needle to influence the great powers of her day. And possibly played a part in the high-stakes game of British diplomacy…

Exile to Enterprise

Esther Inglis was born Esther Langlois (L’Anglois = the English) which is ironic because she and her family were French. They were also committed Protestants — Huguenots — which in sixteenth century France was not a safe option. An estimated 5,000-30,000 Huguenots were killed in a massacre in August 1572. About the time Esther was born, her family fled France for England, and then Scotland.

Esther’s father found a living teaching French in Edinburgh. Esther herself was taught French, English and Latin, as well as needlework and calligraphy by her mother. She picked up bookbinding skills too. You might notice in the painting above she’s holding a small leather volume. There are little fleur-de-lys on the cover, which are a likely reference to her French heritage.

Have a look at the entwined flowers top-left of the picture. A carnation and a honeysuckle — symbols of love. They tell us this was probably an Elizabethan-style marriage portrait.1 No veil, white satin or even a smile in the serious sixteenth century!

In 1596 Esther married Scottish civil servant Bartholomew Kello. Bartholomew also had a traumatic background. His father suffered symptoms of severe mental illness, such as voices and strange dreams. When Bartholomew was still a small boy, his father strangled his wife, Bartholomew’s mother, then faked her hanging. He went off to the Sunday service as usual. Nobody suspected the father of his wife’s death, until he was stricken with remorse and confessed. Bartholomew lost both parents within 10 days.

Wielding Needle and Pen

I think these hardships had an effect on Esther. In her work you can see a sombre awareness of the fragility of life. Although she clearly appreciated its beauty.

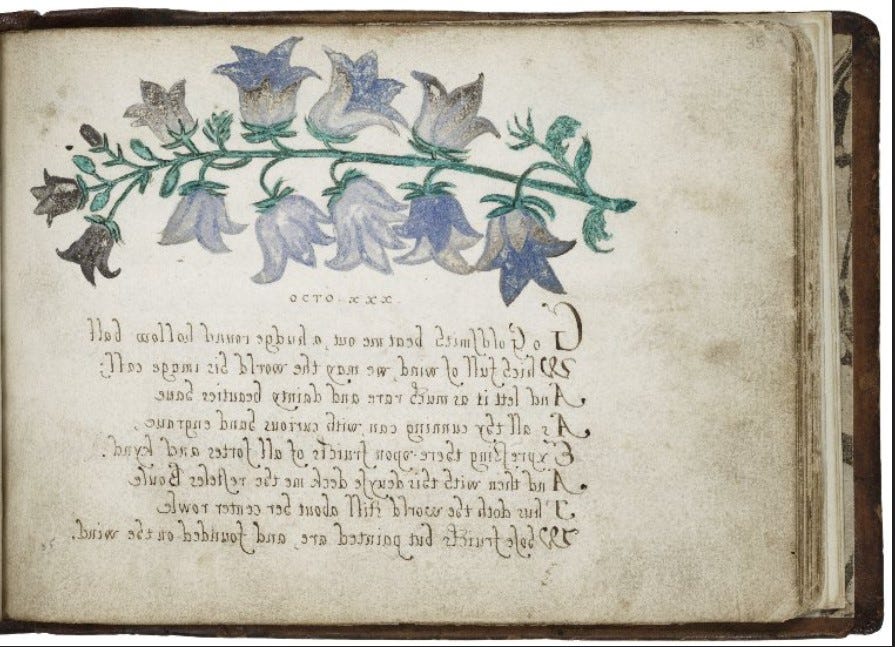

All the pages above and below are her hand-lettered work, even the ones that look printed. And no, the bluebell image isn’t back to front. It’s mirror writing.

The bindings of Esther’s books are as exquisite as the pages. This one is made from crimson velvet, embroidered in silver thread and seed pearls. And it would fit in the palm of your hand — it’s a petite 5cm by 7.6cm (2”x 3”).

Her needle vies with her pen. Esther’s skill beats both — no prize for a winner.

Robert Rollock, principal of Glasgow University2

Around 50 of her books have survived. One of her earliest works was a gift to Queen Elizabeth I, from one literate woman to another. Apparently she made it on spec, encouraged by her parents. Her father wrote an introduction. (In Latin. The Elizabethan era set high standards for literacy.)

This LITTLE BOOK which my dearest Daughter has penned

Accept from her, but with kindness, you glory of this age.

What has prompted my Daughter to make this gift to you?

Your religion, your sex, and your nobility.3

To our ears, the flattery sounds fawning and insincere. But the royals Esther wrote for weren’t just celebrities. They were rulers who decided the fate of individuals and nations. Their disfavour or disregard meant persecution, poverty, prison, or death. The sun did shine out of them, politically speaking.

And aside from the tone of the (lengthy!) dedications, look at the content Esther Inglis put before the readers. The Biblical tracts and poetry are, well, bracing. They’re stern reminders that life is short. Queens and lords aren’t immortal, and they are subject to God.

The beautie of the world goes

As sudden as the wind that bloes

Octo xxviii, Octonaries upon the Vanitie and Inconstancie of the World, 1600

There’s more at stake for Esther than just her own livelihood. For the sake of refugee Protestants like herself, and as a matter of principle, she’s trying to persuade the books’ recipients. She wants them to hold to their faith, for their own good and their nations’.

This heavenly ladder, upon the which I have bestowed a simple ornament… is convenient to be taken in your princely hand and from your hand to be laid up in your heart.

Dedication of the Psalms to 18 year old Scottish Prince Henry

Interestingly, Esther’s husband Bartholomew was no obscure pen-pusher either. He was in fact the ‘Clerk of Passports and Foreign Correspondence’ for King James VI of Scotland. Esther might have loaned her calligraphy and language skills to help her husband’s work. James is known to have carried on secret correspondence with Queen Elizabeth’s court, negotiating his succession to her throne. Very possibly, some of Esther’s books may have been used as gifts in James’ diplomacy. Her art may have paved the way for influential relationships and pro-Protestant decisions.

Esther probably saw that as a worthwhile purpose, in the interests of peace and her principles. I admire her artwork and her determination. Both her needle and her pen had a point.

More bookish recommendations

The State Library of Victoria has a gorgeous online exhibition of old books. That’s where I first found Esther Inglis. My favourite section is the details of how they were made.

There are great descriptions of bookmaking in The Bookbinder of Jericho, a new novel by Australian author Pip Williams. The novel is set at Oxford University Press during WWI. Here’s a video showing Pip hand-binding a copy of her own book:

Or, if you want a tense, well-written tale, based on a true story from the life-and-death politics of the seventeenth century, I recommend Act of Oblivion, by Robert Harris.

From the point of my pen

Lastly, here’s a story poem I wrote based on a recent outing. No connection to any of the above — I just felt like sharing something creative of my own! Maybe in my own way I’m thinking about what happens when people have the wrong stuff ‘laid up in their heart’, as Esther Inglis put it.

(FYI, you need to know that on Melbourne’s transport network, PSO are the security guys — ‘Protective Services Officers’. And there’s a language warning.)

Kids on the Train

Two kids saunter down the train.

They texta-tag the seats

And spoil our peace.

‘I’ll bash ya, c--t!’

A woman mutters, ‘Little shits.’

Their swagger doesn’t fit —

It’s too big, like their black jackets

‘Racked’ from a brand-name store.

‘Run away with me,’ says the girl,

‘I will if you will’.

‘This train is boring,’ says the boy.

For fun, they shut each other

In the rackety link

Between carriages

Where the track flicks dangerous quick

Lickety split —

‘PSOs!’

The train slows

The kids scuttle for an exit.

We stop at station, doors locked, waiting.

The PSOs flank the train’s front.

‘Hope they get them’, says the woman,

But she feels bad they’re young.

I hope to goodness. I’m not sure

Five grown men can catch

Even one slip-sliding soul

Scrambling for the wrong side of the tracks.

Thank you for reading. Feel free to pass this on. And I love hearing your thoughts.

Thanks to the Scottish National Gallery site for these intriguing details.

Translated by Nicolas Barker, on this site.

Glad you liked it! Yes her calligraphy is extraordinary, and I love the embroidered covers. Just a shame the colours fade so badly - before synthetic dyes is the reason I guess.

Fascinating story about Esther Inslish. Talented lady

Your poem reflects some train travel is my guess!