How to Fix your Hay Fever - an eye-watering history

Author Alison Lloyd's Scroll #46 - history with heart

Hay fever is annoying. So annoying that I thought twice about writing this email. Who wants to be reminded of their allergies? Before you chuck this email out with the tissues, you should know that hay fever has an intriguing history. Entertaining even. So let me fix you up good with a dose of historical medicine 🙂

I enjoyed hearing readers’ 1970s memories in response to last month. (If you missed it, 'Feelin Groovy' is here.) This time we’re going back beyond living memory. Scroll down for

how hay fever is not as old-fashioned as it sounds

along with some adventurous cures

and what this funny bit of history might tell us now

The Nose Knows

Hay fever, going by its name, sounds old-fashioned and rural. Actually it’s neither. It’s a pretty new ailment, first recognised during the Industrial Revolution, at least in the west. (Before that, a tenth-century Persian physician named Al-Razi wrote that it was caused by the smell of roses, but his hypothesis went untranslated.)

In 1819, a London doctor named John Bostock wrote an article for the Royal Medical and Chirurgical Society.

Chirurgical — not a typo; the same meaning as ‘surgical’, but more chirrupy and cheerful

The article described a man of ‘spare and rather delicate habit’, named J.B. (i.e. himself). Every June, J.B. sickened with ‘summer catarrh’ — violent sneezing, swollen eyes, tight chest and blocked sinuses. Poor fellow.

Or Does It?

Other nineteenth-century medicos were sceptical of hay fever at first. ‘No one appeared to have witnessed an occurrence of a similar kind,’ Bostock wrote. He himself found only 28 cases in a decade. But the general public thought there was something in it. ‘An idea has very generally prevailed, that it is produced by the effluvium from new hay, and it has hence obtained the popular name of hay fever.’

Effluvium: a lovely Latinate word for odour or discharge

Bostock tried various alarming treatments — bleeding, cold baths, opium and vomiting. Nothing worked. The only way he could escape his symptoms was to live on a clifftop by the sea each summer.

In 1859, another scientist and hay fever sufferer, Charles Blackley, suspected the cause was pollen. He did a series of experiments on himself, putting various pollens up his nose and on his skin. Grass pollens had the (un)desired effect.

How to Dose your Nose

In 1873, Blackley wrote to his friend Charles Darwin:

The problem of the cure has still to be solved…I fear it will prove to be the most formidable and difficult part of the task I originally set myself.

Blackley had plenty of willing help in proposing cures, from the newspapers of the era. The first mention of hay fever in Australian print turns up in 1884:

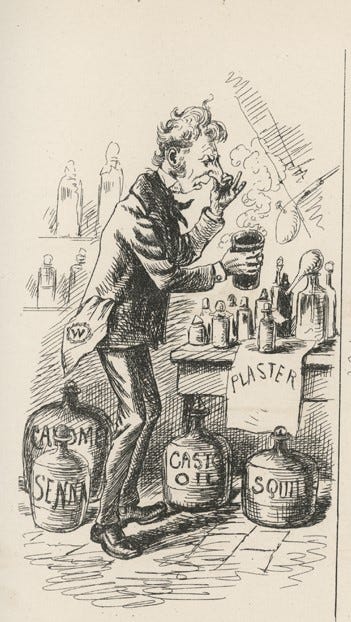

Dr W.T. Philips recommends belladonna (30m. to 3 ounces of water, teaspoonful dose).

Maitland Mercury, 6 November 1884

Belladonna, aka deadly nightshade, can act as a sedative. But it’s also a very effective poison which induces hallucinations. Not a cure to try at home.

This 1887 ‘inhaler’ is basically a glass tube ‘with loose crystals of menthol secured by a perforated cork’. Sufferers put the tube in their mouth or nose and breathed in. The menthol they inhaled is still used in cough drops and has a soothing effect. However, in sufficient amounts, it’s poisonous. While it’s nearly impossible to overdose on cough drops, who knows how potent the crystals were.

A decade later an article suggested, ‘Hay fever may be treated by inhaling the vapours of a pint of hot water to which ten drops of creosote have been added.’ Creosote is that smoky, tarry stuff once used to preserve wood. Sure, that’s a powerful stench which might clear your nose. It’s also cancerous.

If the creosote didn’t work, then:

Some persons find relief by inserting a tabloid of cocaine into the nostrils.

Warwick Argus, 14 August 1897

Wow — medically prescribed snorting! Yes, cocaine numbs your nose, but it also causes nasal ulcers and even perforation of the nasal cartilege. No fun in the long run.

Hay fever was thought to be an ‘aristocratic’ disease. Another regional paper claimed,

‘It is is known only amongst the educated classes, whose nervous systems are highly developed. Many doctors consider it so hopeless of cure they counsel the sufferers to go to the seaside.’

Dungog Chronicle, 25 September 1896

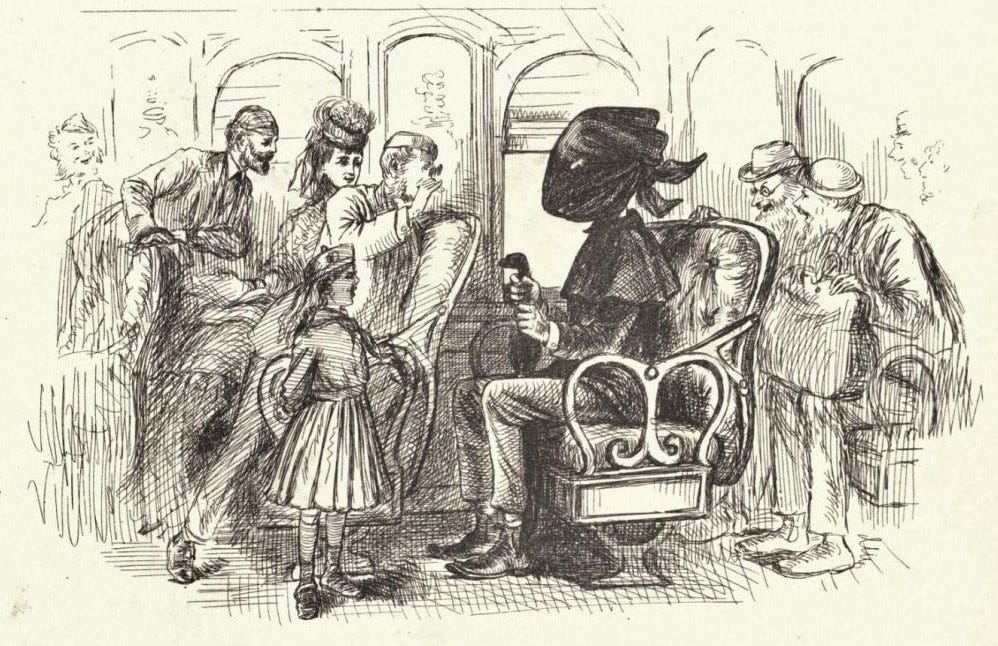

The educated classes liked this advice. Hay fever tourism became quite the rage in Gilded Age America.

In America, hay fever can apparently occur in spring, summer and autumn, depending on your location. (Perhaps you’re are all too aware of that!) In the late nineteenth century, tourist maps were produced showing people where to escape the pollen. Resorts advertised themselves as free of ‘asthmatic difficulties’. The White Mountains in New Hampshire were a popular spot. Mountain hotels hosted up to 500 guests, offering their patrons livery stables, golf courses, a souvenir shop, a telegraph office, and even an orchestra.

The ‘Supper Bell Polka’ below was written in 1858 for Crawford House, one of the biggest and earliest hay fever hotels. Have a listen. It’s a twirly piece, set to historic photos of the resort.

So…

What’s the point of this diversion into medical history? (If you need a point. History doesn’t always have to be serious and worthy. If diversion is all you’re after, stop here.)

We laugh at the cartoons, and raise our eyebrows at the cures. With 21st century knowledge, it’s easy to scoff at the idea that the upper classes have different biology to other humans. It sounds like prejudice. We think we know better.

But do we? Rates of hay fever and allergy skyrocketed over the twentieth century. About one in five Brits now get hay fever — way more than Bostock’s time. We don’t actually know why this is. However, researchers say that, in some countries, the highest risk factor for asthma is dust mite allergy. (Dust mites are those near-invisible critters that lurk in our carpets and furnishings.) Other studies suggest hyper-reactivity in your airways is made worse by long periods of shallow breathing.1

Nowadays, we sit down, and we stay indoors, a lot more than the average non-aristocrat did before the Industrial Revolution. Our rich furnishings and our modern lifestyles are more like the upper classes of previous centuries. So maybe there is something to the notion of hay fever and other allergies being ‘aristocratic’ diseases. And perhaps this itchy bit of history suggests progress can have unforeseen complications, because we don’t know everything.

(Further to that, if you ever think I’m wrong on something, let me know!)

Parting Gifts

Since it’s sneezy Spring in my southern garden, here’s a final bouquet of Australian native blooms for you — virtual and pollen-free!

You may be wondering how my writing is going, and whether you’ll ever see a new book out of me. I admit writing didn’t ‘go’ much last month — we went on a family trip to my husband’s home city in China. If you like Asian history, you can share some of the atmosphere in this short story of mine, set in a Qing dynasty mansion. (It’s free, but you will need to subscribe with your email address.)

As to my Victorian novel, I’m up to the fifth draft, and I’m hoping she’ll be ready to meet readers next year.

Studies cited in ‘The Allergy Epidemics: 1870-2010’ by Dr Thomas A.E. Platt-Mills, sourced via https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4617537/

Thank you for a very entertaining article and especially for the excellent story. You're such a great writer! I've suffered from both hay fever and asthma in my time, and still react to grass pollen at times, but the Victorians were right — living near the sea is a great boon for sensitive lungs. Since moving to Rye I don't need my medicines any more. I told them that at the pharmacy and the pharmacist yanked me into the consulting room and lectured me for 20 minutes on how asthma doesn't go away in adulthood and how I should absolutely continue my medicine (which is now flagged as causing serious side effects) — that's the official stance of today's medicine. What a shame they don't look back at the Victorian wisdom that if your lungs are sensitive to pollution, move away from it. I suppose people would laugh at the notion of a fresh-air sanatorium now, but we're missing a trick.