Let me lavish your day with

some gorgeous golden history you probably didn’t know about

a rare opportunity to peek behind actual closed doors

and a nugget of wisdom

The Big Boom

Once, my home town of Melbourne was one of the world’s richest cities. In the late 1880s, city property prices rivalled London, reaching over £1000 per foot. The well-heeled children of the Gold Rush era needed homes, so swathes of pastoral land were subdivided into suburbs. Builders, agents and speculators made hefty fortunes. Banks popped up like mushrooms around Melbourne, loaning freely and adding more fuel to the boom’s fire. In 1888 there were over 200 banks here.

The Beautiful Bank

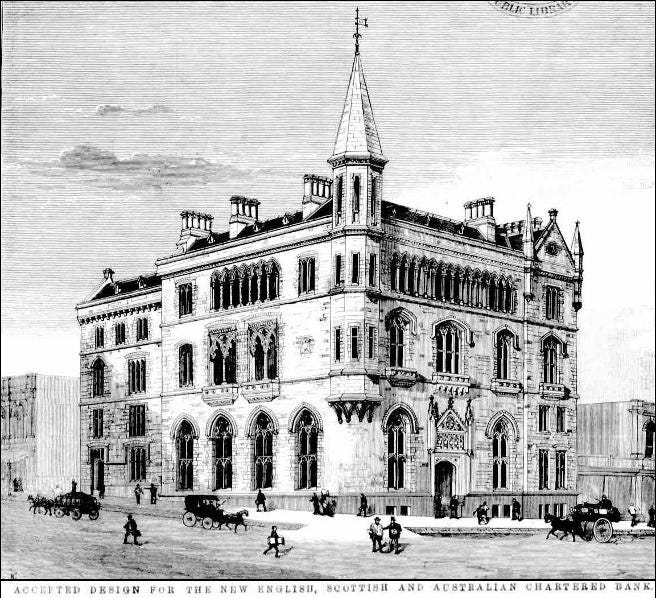

The English, Scottish and Australian Chartered stood proud amongst them. In 1880 the E.S. & A. bought land on Collins Street, the best business address in town, for a substantial £60,000. (Keep in mind that the average bank clerk earned about £200 a year.) At the time, a few single storey, iron-roofed shops fronted an otherwise empty block. But the E.S.& A. had grand plans. Venetian Gothic plans, to be architecturally exact.

The men behind this vision splendid were Victorian E.S.&A. manager Sir George Verdon, and architect William Wardell. It was ‘an unusual relationship’, one historian writes. ‘The banker loved art and architecture more than banking. The architect was better known for designing cathedrals and churches.’ 1

The Busy Banker

Sir George joined the Gold Rush and came to Victoria as a 17-year-old. He failed to find a fortune at the diggings. He set up a business supplying ships in Melbourne, but that also failed ‘with losses great’. He went into politics at the same time, and had more success there. Despite his business record, he was made Treasurer in 1860. Apparently, he 'acquired the esteem and respect of everyone’. He liked to be involved in a bit of everything — astronomy, fine arts, the university and the Royal Society. After politics, his connections came in handy in the banking world.

His project management skills may not have been the best. The building of the new bank ran a year over schedule. When it finally opened in 1887 the final cost of the building had nearly doubled — from a budgeted £42,000 to £77,000. Fortunately for Sir George and the bank, the Victorian economy was still raking it in, and nobody seemed to mind. In fact the bank held an afternoon tea for the workers to thank them.

The result is sumptuous - the Gilded Age at its extravagant and glorious peak. Step inside…

Behind Closed Doors

Upstairs isn’t open to the public. It wasn’t then either, because the second and third floors were the private lodgings of manager Sir George Verdon.

Local journalists were given a tour before he moved in. They described a 6o foot (20m) long drawing room, as well as a dining room, bedrooms, a ‘most ornate and spacious gallery’, a Venetian-style loggia overlooking ‘a wide expanse of country’, a ‘handsomely dressed library’, a conservatory, a billiard room, and even a turret. All ornamented ‘in perfect taste and a triumph of art’.

The ‘wide expanse of country’ has disappeared under steel and concrete. But Verdon’s home has been restored by its current owner. As you can see, he wasn’t feathering his own nest exactly, so much as inlaying, plastering, carving and gilding it. The gold leaf used on the apartment’s ceiling was ‘pure gold leaf and not Dutch or spurious gold of any kind’. So much was used that if it was made into a one-inch strip, the strip would be long enough to ‘reach completely around the world at the equator’.

The Bust — Goodbye to the Gilded Age

You might be thinking you’ve never heard of the English, Scottish and Australian Chartered Bank. A couple of years after the building’s opening, the land boom imploded in a morass of falling prices and unpaid debts. In 1893 the E.S. & A. temporarily suspended payments. It managed to carry on, after a restructure. So did Melbourne, although rents fell by half and a tenth of the population moved away.

The E.S. & A. was finally taken over by the ANZ bank. The Melbourne headquarters were restored to their former glory a century after they were built.

Where you can find hidden riches

The gorgeous extravagance of the bank outlasted the boom that built it. If you’re ever in Melbourne, you can visit the ground floor during business hours at 388 Collins Street.

Also, on 29-30 July 2023 — that’s this month! — you’ve got a chance to see more architectural riches, old and new, if you live nearby. It will be Melbourne’s Open House weekend. Dozens of buildings are opening their doors to the public. More info here.

Stones & Stories

As I was researching the ‘Gothic bank’, I found this quote from a Victorian art critic and advocate for the Venetian Gothic style:

The greatest glory of a building is not in its stones, nor in its gold. Its glory is in its Age, and in that deep sense of voicefulness, of stern watching, of mysterious sympathy...which we feel in the walls...

John Ruskin, The Seven Lamps of Architecture, 1849

I love that. That is exactly how old buildings and ruins make me feel, ‘that deep sense of voicefulness’, as if the stones are full of stories.

He goes on:

It is in their quiet contrast with the transitional character of all things, in the strength which...connects forgotten and following ages with each other.

I think he is onto something there. Grand old buildings, whether the pyramids, a castle, a cathedral, or the Gothic Bank, fill me with awe for their builders and their beauty. But they also make me meditative — aware of the passing of previous eras. They are a reminder of ‘the transitional nature of all things’.

A philosophical note

As it happens, last month I wrote a series of devotionals on the book of Ecclesiastes, in the Bible. The writer was a king who built his own share of grand buildings, but he’s philosophical about our efforts to accumulate wealth and renown.

Vanity of vanities…

All is vanity!

What does man gain by all the toil

at which he toils under the sun?

A generation goes and a generation comes…

There is no remembrance of former things,

nor will there be any remembrance of things yet to be

among those who come after.

Ecclesiastes 1:2-3, 11.

We can’t make anything on earth last forever. We disappear and so do our achievements. It sounds miserable. But Ecclesiastes isn’t saying that there’s no such thing as worth or value. He’s no post-modernist. In fact he says elsewhere that ‘God has made everything beautiful in its time’. He’s just pointing us to a long term perspective — which is what history does too.

Go find a relic of the Gilded Age, or another beautiful building that will speak to you.

If any of this newsletter has struck a chord with you, or you’d like to point me in the direction of your favourite old place, I’d love to hear from you, as always. Reply to this email, give it a like, or post a comment.

Until next month,

Alison L

The Gothic Bank: ANZ’s commitment to preservation. Pamphlet published by ANZ bank, estimated date mid 1990s, held by State Library of Victoria

Sounds like you have a date with destiny to tour the sumptuous apartments of the bank at the end of this month. Recently toured the only surviving sumptuous Victorian/Italianate banking mansion built by the JP Morgan financial empire in New York City. The private library decked out in first editions and decorated in mahogany and leather complete with handcrafted crystal chandeliers attached to the banking chamber was beyond my wildest imaginings. Alas, we're away sailing the Queensland coast or I would join you on this exciting tour. Enjoy!