12 Books to Please your Christmas List

Alison Lloyd's newsletter #47 evaluates 2024's historical fiction prize-winners

Have you started a gift list pre-Christmas? Here’s a round-up of 2024 prize-winning historical fiction, for the readers in your life. Or put them on your own wish list. Many of these books will spark good book club discussions too.

They’re listed in approximate order of how much I like them, because you may as well hear first about the good ones! In my opinionated opinion :) My *favourites* are asterisked. Click on the cover for a link to purchase. (I’m not paid for these recommendations, nor was I given the books, by the way.)

From the UK’s Walter Scott Prize:

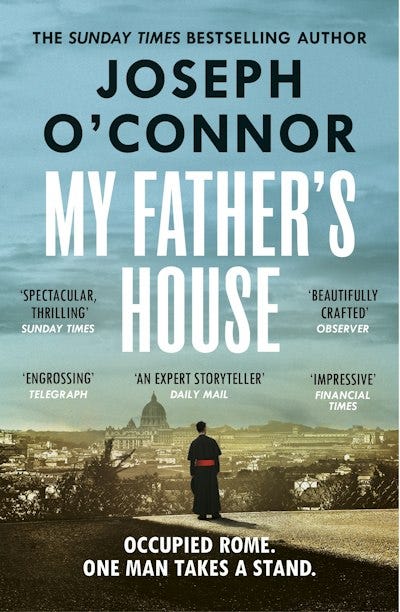

*My Father’s House* by Joseph O’Connor

Set in Nazi-occupied Rome, My Father’s House is based on a true story, about a priest in the Vatican who conducts a ‘choir’ that runs escape routes for POWs. Does that hook you? It did me. The beginning was a little slow — several pages of Irish background went over my Antipodean head — but now I’m turning the pages fast as I can. The characterisations are vivid. Gestapo Commander Hauptmann is ominously convincing, and the clock is ticking down on a high-stakes operation… The operation is to take place on 24 December, even better for a Christmas read.

*Absolutely & Forever* by Rose Tremain

Simon Hearst… was eighteen… and about to take his entrance exam for Oxford. The skin of his face was quite shockingly smooth and beautiful. He liked to let his dark hair flop over his forehead. When I danced with him, I felt as if I was being wafted to eternity. Absolutely and Forever, p1.

Teenage Marianne is perceptive, but insecure and inexperienced. She falls in love ‘absolutely and forever’, with terribly sad consequences for herself and others. Written in first person, the narrative voice is quirky, disarmingly honest, and empathetic. The Walter Scott judges thought it ‘revealed many unspoken truths about women’s lives in the 1960s’. Yes, it’s true that Marianne’s life is constricted by social expectations, but personally I thought the story explored more universal questions about love and need, and I appreciated its emotional nuance.

The rest of the Walter Scott shortlist is here, should you be interested.

The ARA prize is for historical fiction by Australasian authors. Here are its picks:

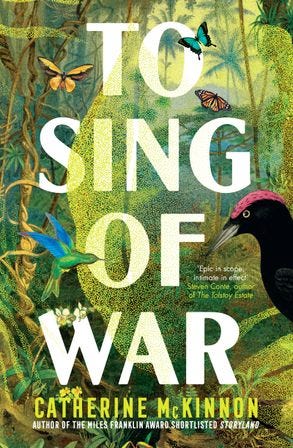

*To Sing of War* by Catherine McKinnon

To Sing of War is what reviewers like to call ‘ambitious in scope’. The closing days of WWII in the Pacific are told from multiple points of view, including an Australian soldier, a nurse, a Japanese civilian and nuclear scientists at Alamos. This structure gives us a sense of the war’s scale and how all-consuming it was. In the New Guinea sections, the relationships between comrades are poignant and absorbing, as is the love story. At Alamos, the proliferation of storylines made for less compelling chapters. Nevertheless, To Sing of War was the book I enjoyed most from the Australian list. There are lyrical and profound moments in Virgil’s narrative particularly. I won’t spoil the end for you by quoting the lines I like most, so here’s a bit from near the beginning instead:

Damp sticks fizz in the fireplace, spill inwards as they burn. Virgil’s hand hovers above the writing pad, pencilled on it two words — Dear Lotte. Ever since their meeting he’s been a galloping horse on an endless track, all thoughts splintering, except this one: write a letter longer than five lines.

To Sing of War, p 6.

Edenglassie by Melissa Lucashenko

Colonial/indigenous conflict has become a frequent theme of Australian historical fiction. Edenglassie is distinctive. It has two timelines, colonial and current, and both are told from Aboriginal perspectives. Lucashenko’s modern characters bubble with personality and humour. The colloquial dialogue is fabulously inventive and fun to read, while making sharp points about indigenous disadvantage. The end is optimistic. I thought this book would win, and it did. I’m not 100% sold on the novel’s final scene, which seems to suggest that only Aboriginal people truly see Australia. Do we believe DNA has that power, even metaphorically?

The Beauties by Lauren Chater

The Beauties has a gorgeous cover and a great story setup — Emilia must become mistress to King Charles II or her husband will lose his land and title. The novel has appropriately lovely prose and I enjoyed its depiction of 17th century England. As it neared the end, I felt like The Beauties was about to say something powerful about justice vs mercy, or guilt and responsibility, or love. But instead it becomes another story about identity and autonomy. ‘You will be the mistress of your own fate,’ someone finally says to Emilia. ‘How does that sound?’ It sounds like a lot of current historical fiction, and left me a little disappointed.

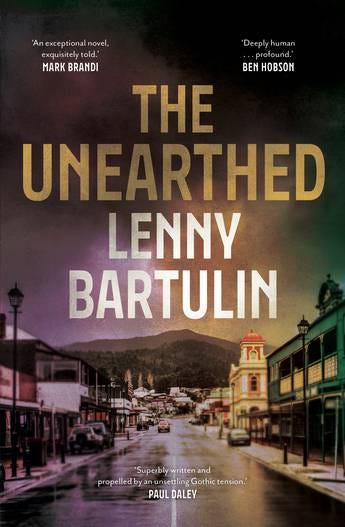

The Unearthed by Lenny Bartulin

Rural noir fans who like their crime on the contemplative side might enjoy The Unearthed. The discovery of human remains in the forest, and an unexpected inheritance, lead us into the personal histories of a Tasmanian mining town. The Unearthed is less a criminal investigation, than it is an exploration of the relationship of past to present, including the fraught relationships of fathers and sons. The novel feels more contemporary-with-flashbacks than historical to me.

Women and Children by Tony Birch

Women and Children is about family life in 1965, ‘in an inner-city suburb with a reputation for hard men and their crimes’. It’s fiction, but with an authentic, autobiographical feel. Birch says it’s a ‘story that witnesses both the trauma of violence and the freedom that comes with summary justice.’ Hmm. I am not persuaded that being a victim of violence justifies taking the law into your hands. (I have the same problem with Rose Tremain’s Lily.) I confess, by the time I started this book, I was already feeling that the awards list was trauma-and-violence heavy. So I skipped a chunk. However, if you like gritty family stories, in spare, evocative prose, this is one for you.

A Better Place by Stephen Daisley

Normally I like stories about brothers. But this one started with a graphic WWII battle scene, and the promise of more trauma in post-war life. I didn’t go past the first chapter.

The Booker Prize Shortlist

This section should really be in parentheses, because I made short work of the Booker’s historical fiction. None of them appealed. (Here’s the whole shortlist including non-historicals.)

Held by Anne Michaels is barely a novel — more an extended poetic musing in twelve fragments scattered across place and time.

The Safekeep by Yael Van der Wouden is a broody story of obsession and repressed desire, set in 1960s Netherlands.

James by Percival Everett is a retelling of Huckleberry Finn. The judges think the book is ‘a towering achievement’ of ‘virtuosic prose’. Since it ‘immerses the reader in the brutality of slavery’, I have no wish to enter its tower. Call me chicken if you like.

Here’s One for Fun

As you can tell, I’m not enamoured of the darkness that typifies this year’s prize lists. All the above books are hefty and serious. This collection needs to lighten up!

So for something fast-paced and fun, how about these opening lines from an Australian longlister:

We were to meet him at midnight in the Dark Walk. It was not an ideal arrangement: two unaccompanied women confronting a blackmailer in the most ill-lit, deserted part of Vauxhall Gardens…

*The Benevolent Society of Ill-Mannered Ladies* by Alison Goodman

A feminist Regency mystery, in which a pair of high society sisters in their 40s turn amateur sleuth. If you’re after a fun holiday read, this is the one to go for. At my library, it has a waitlist longer than a ballgown, so many readers agree.

Too Hard to Choose?

Apparently the more choices we’re given, the more trouble we have deciding. Let’s boil it down to just two, short and simple:

I hope you find something you like amongst these books. Are there other novels you think deserved a shout-out? If you’ve read any of the above, I’d love to hear what you think, especially if you disagree.

You are welcome to pass this info on:

Happy reading until next month, when I look forward to bringing you Christmas writing of my own.