Surprising stories from the early Olympics

Author Alison Lloyd's newsletter #43

The 2024 Olympics are set to start. I love the athletics and the gymnastics — the amazing feats of mid-air motion. I like underdog stories too, in any sport. Which event are you looking forward to?

Limber up in this Scroll with:

surprising stories of historic athletes

And some refreshing new fiction! About a fictional swim.

The first female Olympic champion was deaf

In 1900, the second modern Olympics were held in the same city as this year — Paris. The Olympics were timed to coincide with an international Exposition. Here’s a short of some fabulous old footage, re-colourised:

Charlotte Cooper Sterry (1870-1966) was a British tennis player who lost her hearing in her twenties. Despite that disability, and a long white dress, she rode her bicycle off to Wimbledon. She came home with the women’s title. She won Wimbledon three times, in 1895, 1896, and 1898, before going to the 1900 Olympics, where she won the women’s singles and the mixed doubles.

Australia’s first women Olympians make ripples

Australia’s first female Olympians were swimmers. No surprise there! Like their modern Aussie team mates, Fanny Durack and Mina Wylie did well in the water. In the Stockholm Olympics of 1912, they took out gold and silver in the 100m freestyle.

But they almost didn’t make it to the games. 1912 was the first time women’s swimming was included as an Olympic event. Back home in Australia, women weren’t allowed to swim with men at public pools, and men weren’t allowed to watch women compete. (You can see why if you compare the 1912 swim suits with earlier Victorian models. Those clingy curves!)

Fanny Durack went on to set 12 world records between 1912-1918. Her fastest time was 1 minute 16.2 seconds for 100m. Now the record is down to 51.01 seconds, set a century later by another Australian, Libby Trickett, in 2009.

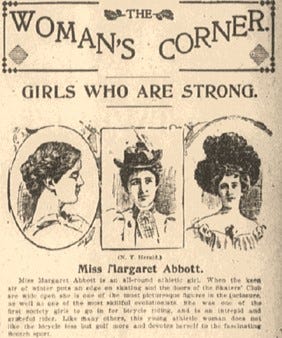

America’s first woman what?

Margaret Abbott came to Paris from Chicago with her mother Mary in 1900, to study art. Mother and daughter also enjoyed playing golf. So when the women heard of an international tournament about to be held locally, they decided to enter.

Margaret Abbott shot 47 on a 9-hole course to come first. Mary Ives Abbott came 7th. Margaret won a gold-mounted porcelain bowl. She didn’t get a medal. In fact, she never realised the tournament was part of the Olympic Games. Margaret Abbott was actually America’s first female Olympic champion, and never knew it. A researcher eventually figured out the significance of her win in the 1980s.

Which brings me to a point I feel is worth remembering as the medal count mounts. Olympic fame isn’t a good measure of what matters. IRL, in our non-Olympic lives, the finish line keeps shifting — when you think a thing’s done something else pops up. And our stumbling, ungraceful efforts are often unsung. No medal ≠ no value. You can be a champion without realising.

All Thy Waves and Thy Billows

Now for the promised new short fiction from me. Nobody else has read this, so I’d welcome any feedback, whether it’s what you liked, or parts that don’t read well, or don’t make sense.

The story is a kind of prequel to the novel I’m writing, which is set in 1888. The main character, Amaryllis (Ryll for short) is affected by polio when she’s thirteen…

The summer after Ryll was sick and her cousin Bucky died, grief pressed on their family in relentless heat. Infantile paralysis, the doctor called it. The fever drained from the children’s bodies into the air, where it clogged every movement. Melbourne’s shaded rooms felt like coffins.

Ryll lay on her bed, her twisted left leg and cramped hand covered with a sheet. She felt like a cat she had seen once, struck by a cart – no blood to be seen, but the shape was wrong.

Cousin Ed came to see her after Bucky’s funeral. ‘If you stay here,’ she whispered, ‘you might die.’

Ryll knew that. Her right leg had sort of died already. It couldn’t take her weight. She had to be carried to the commode although she was much too old to be toileted, and the humiliation of it burned hotter than her yellow pee.

Ryll’s parents disappeared inside themselves. They came in and out of her room, like the empty cabs that crunched along the street outside, pulled by listless, twitching horses, trundling through the day without a fare or a purpose.

Mamma was too worn down by the heat and their losses to resist when Ed proposed a trip to the bay. With her fourteen-year-old fortitude, Ed hailed a passing hansom. She bossed her remaining three brothers and Ryll’s sister Daphne into it. She and the nursemaid carried Ryll out, hefted her up and laid her along one seat.

‘She’s war-wounded!’ Five-year-old Tim observed, awestruck. Bucky had fed his brothers an educational diet of heroic stories.

Ed shushed him, but Ryll smiled.

Even with the windows down, the cab was suffocating, sticky with the smell of children’s sweat. At the bay, the boys piled out, dodging between promenaders, while the cabbie lowered Ryll into the arms of her cousin and Nancy, the maid. A line of perspiration dribbled along Ed’s neck onto the sailor collar of her bathing costume. She and Nancy staggered to the sand with their burden.

‘We oughtta be firefighters, miss,’ Nancy puffed. ‘This is how they rescue people int it?’

‘Feels hot enough!’ Ed agreed. ‘Boys, wait!’

The cousins had dumped everything – hamper, hats, shoes and socks, buckets, spades, toy sailboat, ball, parasol – the whole picnic paraphernalia was discarded willy nilly, as they bolted wildly for the water. Daphne chased barefoot after the boys, holding her hat on with one hand, blonde hair flying like a pony’s mane.

‘Little heathens,’ Nancy said, almost enviously. Nancy wasn’t very old either, but she was older than Ed. She looked at the zigzag of discarded picnic stuff with a little sniff. ‘We’d best pick that up,’ she told Ed.

‘But the boys!’ Ed was chomping on her lip. She was stuck between her responsibility for her brothers, and for Ryll. ‘I can’t lose any of them. I just can’t.’ Her cheeks were flaming red.

‘I don’t want to lose me job neither,’ Nancy said, turning her head to search for strayed possessions.

‘I’ll be alright,’ Ryll said. ‘You can put me here.’

Ed and Nancy lowered her to the sand.

‘I’ll be back in a moment,’ Ed said, ‘when Nancy’s done.’

Nancy took her time. She sauntered along, collecting the bits and pieces, surveying the beach, the ladies and the lads.

Ryll was left sitting on her own. She felt the sea air touch her cheek. The sky was so wide and so blue around her that its intensity made her want to cry. She’d been behind drawn blinds for so long. It was a relief to know there was a world outside.

In front of her, the rhythm of the waves was like a dance – forward, bow to your partner, out again. Ed was in up to her shins, marshalling Daphne and Nancy to mind Tim, the youngest, and hollering to the older ones not to go too deep. Daphne chopped her hand sideways at the water the way the boys had taught her, but she got Nancy instead of Ed. Nancy shrieked, and chopped back. Ed laughed, and then they were all at it. Everyone was having a fine time.

Just up the beach, a game of cricket had changed batters and was now encroaching on Ryll’s spot. The ball came off the new batter’s stroke with a crack, sailing high, then dropping straight for Ryll. A fielder backed up, his hands cupped and his eyes on the ball.

‘Hey – watch out!’ Ryll called, as he was about to step on her.

The fielder swerved, showering her with sand, and missing the catch.

‘Move why don’t ya?’ He threw the words back over his shoulder, as he scooped up the ball.

Ryll sat in the shimmering bath of light that bounced off the white sand. It lathered her head to toe with heat. Even when she closed her eyes the light was gritty and sharp like diamonds on her lids. The beach smelt of rotting seaweed, and wet dog. Suddenly it was horrible, and she wanted to go home, back to the shade.

Ed came stomping up the beach with her clumpy, un-girlish walk that Ryll had once thought embarrassing.

‘Isn’t it wonderful?’ Ed spread her arms. ‘All this space to run around in!’ Ed was doggedly cheerful. It was a funny gift she had.

‘Oh yes,’ Ryll said, sarcastically, so Ed would not notice that she wanted to cry.

But Ed heard. She knelt before Ryll and peered under the brim of her hat. She clapped a hand over her mouth. ‘I’m so sorry! What a booby! I didn’t think. Of course you can’t…’

Of course Ryll couldn’t. She couldn’t stand by herself. Running around was out of the question. The doctor prescribed rest. But the more Ryll lay in bed, the more she felt like a melting blob. Even her good leg was shaky when Mamma helped her up.

‘What about swimming?’ Ed was enthusiastic. ‘The doctor never said anything about not swimming, did he?’

Another wave scrambled up the beach, reached for them, and withdrew. The tide was coming in.

‘It’s not far,’ Ed coaxed, ‘just to the edge. And it’s so nice.’ Ed had her find-a-way-to-do-this look. ‘What if you leaned on me, with your arm around my neck – like the war-wounded? I’m pretty strong.’

Ed was a great admirer of someone called Amelia Bloomer. Ed’s father thought ‘Bloomer suits’ were outlandish, even at home, but he indulged her passion for healthful exercise to the extent of buying her the bathing costume.

‘Aren’t you afraid of the sea?’ Ryll asked.

‘Not the shallow bits. But since – since you know what – I’m afraid of more things than I used to be.’ Ed chewed her lip again. She held Ryll’s hand as if she needed to keep her from going somewhere. ‘It’s like I was splashing around in the shallow water before, and I didn’t realise the deep was about to hit us. Now I know it’s there. I can’t quite forget it. Which is silly, because Bucky –’ she stumbled over his name ‘– wasn’t drowned. But still. Deep calleth unto deep. All that.’

She was quoting the Bible they’d heard in church, that thick black book with its own sea of words. Let us remember our dear departed… Ed wasn’t silly. Ryll knew what she meant.

The sea had never been her favourite place – all the pushing and pulling. ‘I don’t want to go in,’ she said.

‘Salt water is thought to be recuperative!’ Ed said brightly.

Not if you drown, Ryll thought. She didn’t have the strength to resist the waves.

Ed twisted her hat ribbon around her forefinger, so tightly that her finger went red and white. ‘Please Ryll. You’re so pale, you know. Like a ghost. I just want you to come back to life. Please.’

Ryll saw her cousin was on the edge of tears too, clinging to the rock of the living. They were both war-wounded.

So she said yes. Ed helped Ryll strip her shoes and stockings. Then Ryll looped her arm over Ed’s sticky neck, and let her cousin reach her sandy forearm around Ryll and heave her off the sand. They hopped and dragged and staggered to the waterline.

The wet sand was soothingly cool and tactile on Ryll’s feet. The edge of the incoming waves lapped her ankles with a wonderful chill, like the first lick of ice-cream.

‘You see?’ Ed crowed.

Even the air was cooler over the water.

A few feet ahead, in knee-deep wash, Tim balanced on his hands, thrashing his feet and pretending to swim.

‘Amaryllis! Look at me!’ He beckoned madly, then copped a face full of frothy breaker. His brothers and Daphne laughed at him from where they lounged in the roll of incoming waves. Nancy pulled him up again and wiped him over with her sleeve. He spluttered and coughed, then threw himself back to swimming.

Without asking, Ed towed Ryll further in, knee deep, until the bottom half of Ryll’s skirt was wet. The heavy cotton swirled around her knees as a wave sucked out. Her bad foot swished about like a piece of hooked seaweed.

‘It’s too deep,’ she said.

‘No it isn’t.’ Ed was firmly planted in the sand, the length of her body hot and solid against Ryll. The sea drained away, the water running between their toes like silk.

But it came back, in a long roll that broke right on them, thigh-high. It lifted Ryll’s feet from her, and tossed her under, thrashing her about like a branch of kelp, her dress and limbs writhing in the rush of water.

No, no, no. She hit out at the water, slicing at the currents, straining to get her head up.

And then the wave dumped her like a shipwreck in the shallows. Ryll spat burning salt from her mouth and peeled her hair from her face.

Ed waded towards her, splashing furiously. ‘Look at you!’ she shouted. ‘You were kicking! Kicking!’

‘I’m not Tim!’ Ryll said. She wasn’t an infant to be watched and petted.

But she’d felt it. The desperate twitch. The sensation of her muscles fighting for life. Her skin tingled, as if the sea had pummelled its energy into her.

Tim retrieved her mangled hat and handed it back. ‘You alright, Amaryllis?’

‘Yes, I’m alright. You?’

He nodded vigorously. Under the freckles of sand, he was shivering, either with cold or excitement or both.

Ed helped Ryll to her feet again. ‘We’ll come every day,’ Ed resolved. Drops of water sparkled on her cheeks, and her face was keen with hope and determination. ‘Until you can stand by yourself.’

Yes, they would, Ryll thought. All the cousins would pile into a hot, leathery cab, and come to the sea. Until the memories of the fever, her torpor, and the abscess where Bucky had been, were bleached in the briney wash of the ocean. Until their clean bones and their lean, living muscles swum them all back to shore. The deep gave life, as well as death.